ATESTAT LIMBA ENGLEZA

Table contents

ARGUMENT....................4

SAINT PATRICKS` DAY..............5

CELEBRATIONS..................5

RECENT HISTORY................6

SHAMROCK...................7

WHO WAS SAINT PATRICK?...........11

TAKEN PRISONER BY IRISH RAIDERS.......11

GUIDED BY VISIONS...............12

BONFIRES AND CROSSES............12

PATRICK IN HIS OWN WORLD.........13

DATING PATRICK`S LIFE AND

THE FIRST PARADE.................16

NO IRISH NEED APPLY..............16

WEARING OF THE GREEN GOES GLOBAL....17

THE PARADE.................17

THE

THE SHAMROCK................18

THE LEPRECHAUN...............19

THE SNAKE....................19

IRISH MUSIC..................19

ST. PATRICK`S DAY RECIPES...........21

IRISH SODA BREAD WITH RAISINS........21

IRISH BROWN BREAD.............22

CORNED BEEF AND CABBAGE...........23

CHAMP......................24

BEEF AND GUINESSE PIE............25

IRISH CREAM CHOCOLATE..........26

MOUSSE.....................27

CAKE.......................27

SYRUP.....................28

CHOCOLATE BANDS...............28

CHOCOLATE CURLS........,......28

CONCLUSION.................29

BIBLIOGRAPHY..................30

ARGUMENT

1. SAINT PATRICKS` DAY

Saint Patrick's Day (Irish: Lá 'le Pádraig or Lá Fhéile Pádraig), colloquially St. Paddy's Day or Paddy's Day, is an annual feast day which celebrates Saint Patrick (circa 385-461), one of the patron saints of Ireland. It takes place on 17 March, the date on which Patrick is held to have died.

The day is the national

holiday of the Irish people. It is a bank holiday in

It became a feast day in the

Roman Catholic Church due to the influence of the Waterford-born Franciscan

scholar Luke Wadding in the early part of the 17th century, and is a holy day

of obligation for Roman Catholics in

1.2 Celebration

Saint Patrick's Day is

celebrated worldwide by Irish people and increasingly by many of non-Irish

descent (usually in

It was also on St. Patrick's

Day that

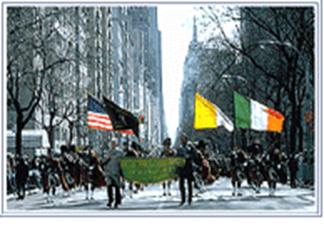

The St. Patrick's Day parade

in

Other large parades include

those in Savannah, Georgia , New London, Wisconsin (which changes its name to

New Dublin the week of St. Patrick's Day), Dallas, Cleveland, Manchester,

Birmingham, London, Coatbridge, Montreal (the longest continually running St.

Patrick's Day parade, celebrating its 183rd consecutive parade in 2007),

Jackson, Mississippi, Boston, Houston, Chicago, Cincinnati, Kansas City,

Philadelphia, Indianapolis, Pittsburgh, Denver, St. Paul, Sacramento, San

Francisco, Scranton, Seattle, Butte, Detroit, Toronto, Vancouver, Syracuse,

Newport, Holyoke and throughout much of the Western world. The parade held in

As well as being a celebration

of Irish culture, Saint Patrick's Day is a Christian festival celebrated in the

Catholic Church, the

In many parts of North America, Britain, and Australia expatriate Irish, those of Irish descent, and ever-growing crowds of people with no Irish connections but who may proclaim themselves "Irish for a day" also celebrate St. Patrick's Day, usually by drinking larger amounts of alcoholic beverages (lager dyed green, Irish beer and stout, such as Murphys, Beamish, Smithwicks, Harp or Guinness, or Irish whiskey, Irish cider, Irish coffee, or Baileys Irish Cream) than they normally would, and by wearing green-coloured clothing. The eating of Irish soda bread (which is sold in supermarkets for the occasion, but not sold during the rest of the year except in specialty stores) is also common. Some recent American twists on the holiday, reflecting its growing popularity among the non-Irish, are the making and selling of green bagels and popcorn on and near the day.

2007 marked the first annual

St. Patrick's Day parade and festival in the Scottish city of

1.3 Recent history

In the recent past, Saint

Patrick's Day was celebrated only as a religious holiday. It became a public

holiday in 1903, by the Bank Holiday (

Sign on a beam in the Guinness Storehouse.

It was only in the mid-1990s

that the Irish government began a campaign to use Saint Patrick's Day to

showcase

-Offer a national festival that ranks amongst all of the greatest

celebrations in the world and

promote excitement throughout

via innovation, creativity, grassroots involvement, and marketing activity.

-Provide the opportunity and motivation for people of Irish descent, (and

those who sometimes wish they were Irish) to attend and join in the

imaginative and expressive celebrations.

-Project, internationally, an accurate

image of

professional and sophisticated country with wide appeal, as we approach the

new millennium.

The first Saint Patrick's Festival was held on 17 March, 1996. In 1997, it became a three-day event, and by 2000 it was a four-day event. By 2006, the festival was five days long. The topic of the 2004 St. Patrick's Symposium was "Talking Irish," during which the nature of Irish identity, economic success, and the future were discussed. Since 1996, there has been a greater emphasis on celebrating and projecting a fluid and inclusive notion of "Irishness" rather than an identity based around traditional religious or ethnic allegiance. The week around Saint Patrick's Day usually involves Irish speakers using more Irish during seachtain na Gaeilge ("Irish Week").

1.4 Shamrock ("three-leaf-clover")

Many Irish people still wear a bunch of shamrocks on their lapels or caps on this day or green, white, and orange badges (after the colours of the Irish flag). Girls and boys wear green in their hair. Artists draw shamrock designs on people's cheeks as a cultural sign, including American tourists.

Although Saint Patrick's Day has the colour green as its theme, one little known fact is that blue was once the colour associated with this day.

The biggest celebrations on

the

The day is celebrated by the

Since the 1990s, Irish Taoisigh have sometimes attended special functions either

on Saint Patrick's Day or a day or two earlier, in the White House, where they

present shamrock to the President of the United States. A similar presentation

is made to the Speaker of the House. Originally only representatives of the

Republic of Ireland attended, but since the mid-1990s all major Political

parties in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland are invited, with the

attendance including the representatives of the Irish government, the Ulster

Unionist Party, the Social Democratic and Labour Party, Sinn Féin and others. No Northern Irish parties

were invited for these functions in 2005. In recent years, it is common for the

entire Irish government to be abroad representing the country in various parts

of the world. In 2003, the President of Ireland celebrated the holiday in

Sydney, the Taoiseach was in

Saint Patrick's Day parades in

Christian leaders in

2. Who Was Saint Patrick?

St. Patrick, the patron saint

of

Many of the

stories traditionally associated with St. Patrick, including the famous account

of his banishing all the snakes from

Somewhat of a

mystery. Many of the stories traditionally associated with St. Patrick,

including the famous account of his banishing all the snakes from

2.2 Taken Prisoner by Irish Raiders

It is known that

St. Patrick was born in

2.3Guided by Visions

After more than

six years as a prisoner, Patrick escaped. According to his writing, a voice-which

he believed to be God's-spoke to him in a dream, telling him it was time to

leave

To do so, Patrick

walked nearly 200 miles from

2.4 Bonfires and Crosses

Familiar with the Irish language and culture, Patrick chose to incorporate traditional ritual into his lessons of Christianity instead of attempting to eradicate native Irish beliefs. For instance, he used bonfires to celebrate Easter since the Irish were used to honoring their gods with fire. He also superimposed a sun, a powerful Irish symbol, onto the Christian cross to create what is now called a Celtic cross, so that veneration of the symbol would seem more natural to the Irish. (Although there were a small number of Christians on the island when Patrick arrived, most Irish practiced a nature-based pagan religion. The Irish culture centered around a rich tradition of oral legend and myth. When this is considered, it is no surprise that the story of Patrick's life became exaggerated over the centuries-spinning exciting tales to remember history has always been a part of the Irish way of life.)

2.5 Patrick in His Own Words

Slemish,

Slemish,

Two Latin letters survive which are generally accepted to have been written by Patrick. These are the Declaration (Latin: Confessio) and the Letter to the soldiers of Coroticus (Latin: Epistola). The Declaration is the more important of the two. In it Patrick gives a short account of his life and his mission.

Patrick was born at Banna

Venta Berniae, Calpornius his father was a deacon, his grandfather Potitus a

priest. When he was about sixteen, he was captured and carried off as a slave

to

I saw a men coming, as it were

from

Much of the Declaration concerns charges made

against Patrick by his fellow Christians at a trial. What these charges were,

he does not say explicitly, but he writes that he returned the gifts which

wealthy women gave him, did not accept payment for baptisms, nor for ordaining

priests, and indeed paid for many gifts to kings and judges, and paid for the

sons of chiefs to accompany him. It is concluded, therefore, that he was

accused of some sort of financial impropriety, and perhaps of having obtained

his bishopric in

From this same evidence, something can be seen of Patrick's mission. He writes that he "baptised thousands of people". He ordained priests to lead the new Christian communities. He converted wealthy women, some of whom became nuns in the face of family opposition. He also dealt with the sons of kings, converting them too.

Patrick's position as a

foreigner in

Murchiú's life of Saint Patrick contains a supposed prophecy by the druids which gives an impression of how Patrick and other Christian missionaries were seen by those hostile to them:

Across the sea will come Adze-head, crazed in the head, his cloak with hole

for the head, his stick bent in the head.

He will chant

impieties from a table in the front of his house; all his people

will answer: "so be it, so be it."

The second piece of evidence

from Patrick's life is the Letter to

Coroticus or Letter to the

Soldiers of Coroticus. In this, Patrick writes an open letter announcing

that he has excommunicated certain British soldiers of Coroticus who have

raided in

2.6 Dating Patrick`s Life and Mission

According to the latest reconstruction of the old Irish annals, Patrick died in AD 493, a date accepted by some modern historians. Prior to the 1940s it was believed without doubt that he died in 461 and thus had lived in the first half of the 5th century. A lecture entitled "The Two Patricks", published in 1942 by T. F. O'Rahilly, caused enormous controversy by proposing that there had been two "Patricks", Palladius and Patrick, and that what we now know of St. Patrick was in fact in part a conscious effort to meld the two into one hagiographic personality. Decades of contention eventually ended with most historians now asserting that Patrick was indeed most likely to have been active in the mid-to-late 5th century.

While Patrick's own writings contain no dates, they do contain information which can be used to date them. Patrick's quotations from the Acts of the Apostles follow the Vulgate, strongly suggesting that his ecclesiastical conversion did not take place before the early fifth century. Patrick also refers to the Franks as being pagan. Their conversion is dated to the period 496-508.

The compiler of the Annals of Ulster stated that in the year 553:

I have found this in the Book

of Cuanu: The relics of Patrick were placed sixty years after his death in a

shrine by Colum Cille. Three splendid halidoms were found in

the burial-place: his goblet, the Angel's Gospel, and the

The reputed burial place of St. Patrick in Downpatrick.

The placing of this event in the year 553 would certainly seem to place Patrick's death in 493, or at least in the early years of that decade, and indeed the Annals of Ulster report in 493:

Patrick arch-apostle, or archbishop an apostle of the Irish, rested on the 16th of

the Kalends of April in the 120th year of his age, in the 60th year after he had

come to

There is also the additional evidence of his disciple, Mochta, who died in 535.

St. Patrick is said to be

buried under Down Cathedral in Downpatrick,

2.7 The First Parade

On St. Patrick's Day, which falls during the Christian season of Lent, Irish families would traditionally attend church in the morning and celebrate in the afternoon. Lenten prohibitions against the consumption of meat were waived and people would dance, drink, and feast-on the traditional meal of Irish bacon and cabbage.

The

Over the next thirty-five years, Irish patriotism among American immigrants flourished, prompting the rise of so-called "Irish Aid" societies, like the Friendly Sons of Saint Patrick and the Hibernian Society. Each group would hold annual parades featuring bagpipes (which actually first became popular in the Scottish and British armies) and drums.

2.8 No Irish Need Apply

Up until the

mid-nineteenth century, most Irish immigrants in

However, the

Irish soon began to realize that their great numbers endowed them with a

political power that had yet to be exploited. They started to organize, and their

voting block, known as the "green machine," became an important swing

vote for political hopefuls. Suddenly, annual St. Patrick's Day parades became

a show of strength for Irish Americans, as well as a must-attend event for a

slew of political candidates. In 1948, President Truman attended

2.9 Wearing of the Green Goes Global

Today, St.

Patrick's Day is celebrated by people of all backgrounds in the

In modern-day

Beginning

in 1995, however, the Irish government began a national campaign to use St.

Patrick's Day as an opportunity to drive tourism and showcase

2.10The Parade

In 1848, several

New York Irish aid societies decided to unite their parades to form

In 1848, several

New York Irish aid societies decided to unite their parades to form

Each year, nearly three million people line the

one-and-a-half mile parade route to watch the procession, which takes more than

five hours.

Chicago is also famous

for a somewhat peculiar annual event: dyeing the

Today,

in order to minimize environmental damage, only forty pounds of dye are used,

making the river green for only several hours. Although

They point out that 1961, Savannah mayor Tom Woolley had plans for a green river, but due to rough water on March 17, the experiment didn't work and Savannah never attempted to dye.

In fact the first written mention of this story did not appear until nearly a thousand years after Patrick's death.

The

shamrock, which was also called the "seamroy" by the Celts, was a

sacred plant in ancient

The original Irish name for these figures of folklore is "lobaircin," meaning "small-bodied fellow."

Belief in leprechauns probably stems from Celtic belief in fairies, tiny men and women who could use their magical powers to serve good or evil. In Celtic folktales, leprechauns were cranky souls, responsible for mending the shoes of the other fairies. Though only minor figures in Celtic folklore, leprechauns were known for their trickery, which they often used to protect their much-fabled treasure.

Leprechauns

had nothing to do with St. Patrick or the celebration of St. Patrick's Day, a

Catholic holy day. In 1959, Walt Disney released a film called Darby O'Gill

& the Little People, which introduced

It has long been

recounted that, during his mission in

In

fact, the island nation was never home to any snakes. The "banishing of

the snakes" was really a metaphor for the eradication of pagan ideology

from

Irish Music

Music is often associated with St. Patrick's Day-and Irish culture in general. From ancient days of the Celts, music has always been an important part of Irish life. The Celts had an oral culture, where religion, legend, and history were passed from one generation to the next by way of stories and songs.

After being conquered by the English, and forbidden to speak their own language, the Irish, like other oppressed peoples, turned to music to help them remember important events and hold on to their heritage and history. As it often stirred emotion and helped to galvanize people, music was outlawed by the English. During her reign, Queen Elizabeth I even decreed that all artists and pipers were to be arrested and hanged on the spot.

Today, traditional Irish bands like The Chieftains, the Clancy Brothers, and Tommy Makem are gaining worldwide popularity. Their music is produced with instruments that have been used for centuries, including the fiddle, the uilleann pipes (a sort of elaborate bagpipe), the tin whistle (a sort of flute that is actually made of nickel-silver, brass, or aluminum), and the bodhran (an ancient type of frame drum that was traditionally used in warfare rather than music).

Nonstick vegetable oil spray

2 cups all purpose flour

5 tablespoons sugar, divided

1 1/2 teaspoons baking powder

1 teaspoon salt

3/4 teaspoon baking soda

3 tablespoons butter, chilled, cut into cubes

1 cup buttermilk

2/3 cup raisins

Preheat oven to 375°F. Spray 8-inch-diameter cake pan with nonstick spray.

Whisk flour, 4 tablespoons sugar, baking powder, salt, and baking soda in large

bowl to blend. Add butter.

Using fingertips, rub in until coarse meal forms. Make well in center of

flour mixture. Add buttermilk. Gradually stir dry ingredients into milk to

blend. Mix in raisins.

Using floured hands, shape dough into ball. Transfer to prepared pan and

flatten slightly (dough will not come to edges of pan). Sprinkle dough with

remaining 1 tablespoon sugar.

Bake bread until brown and tester inserted into center comes out clean, about

40 minutes. Cool bread in pan 10 minutes. Transfer to rack. Serve warm or at

room temperature.

2 cups whole-wheat flour

2 cups all-purpose flour plus additional for kneading

1/2 cup toasted wheat germ

2 teaspoons salt

2 teaspoons sugar

1 teaspoon baking soda

1/2 teaspoon cream of tartar

1 stick (1/2 cup) cold unsalted butter, cut into 1/2-inch cubes

2 cups well-shaken buttermilk

Put oven rack in middle position and preheat oven to 400°F. Butter a 9- by

2-inch round cake pan.

Whisk together flours, wheat germ, salt, sugar, baking soda, and cream of

tartar in a large bowl until combined well. Blend in butter with a pastry

blender or your fingertips until mixture resembles coarse meal. Make a well in

center and add buttermilk, stirring until a dough forms. Gently knead on a

floured surface, adding just enough more flour to keep dough from sticking,

until smooth, about 3 minutes.

Transfer dough to cake pan and flatten to fill pan. With a sharp knife, cut an

X (1/2 inch deep) across top of dough (5 inches long). Bake until loaf is

lightly browned and sounds hollow when bottom is tapped, 30 to 40 minutes. Cool

in pan on a rack 10 minutes, then turn out onto rack and cool, right side up,

about 1 hour.

Cooks' notes:

" Bread can be served the day it is made, but it slices more easily if

kept, wrapped in plastic wrap, at room temperature 1 day.

" Leftover bread keeps, wrapped in plastic wrap, at room temperature 4

days.

3.5 CHAMP

3.7 IRISH CREAM CHOCOLATE MOUSSE CAKE

This rich chocolate mousse cake was created by Geri Gilliland, the Belfast-born

chef-owner of Gilliland's, a cafe with an Irish accent in

3.8 Mousse

4 large eggs

1/3 cup sugar

12 ounces semisweet chocolate, chopped

1 1/2 cups chilled whipping cream

1/4 cup Irish cream liqueur

Whisk eggs and sugar in large metal bowl. Set bowl over saucepan of simmering

water (do not allow bottom of bowl to touch water) and whisk constantly until

candy thermometer registers 60°F, about 5 minutes.

Remove bowl from over water. Using electric mixer, beat egg mixture until cool

and very thick, about 10 minutes.

Place chocolate in top of another bowl over simmering water; stir until melted

and smooth. Remove bowl from over water. Cool to lukewarm.

Combine cream and Irish cream liqueur in medium bowl; beat to stiff peaks. Pour

lukewarm melted chocolate over egg mixture and fold together. Fold in cream

mixture. Cover and chill until set, at least 4 hours or overnight.

3.9 Cake 6 large eggs

3/4 cup plus 2 tablespoons sugar

2 tablespoons instant espresso powder or coffee powder

Pinch of salt

1 cup all purpose flour

Preheat oven to 350°F. Butter 9-inch-diameter spring form pan with 2

3/4-inch-high sides. Line bottom with parchment paper. Using electric mixer,

beat eggs, sugar, espresso powder and salt in large bowl until mixture thickens

and slowly dissolving ribbon forms when beaters are lifted, about 8 minutes.

Sift 1/3 of flour over and gently fold into egg mixture. Repeat 2 more times

(do not overmix or batter may

deflate).

Pour batter into prepared pan. Bake until tester inserted into center comes out

clean, about 35 minutes. Cool cake completely in pan on rack.

Run small sharp knife around pan sides to loosen cake. Release pan sides. Turn

out cake. Remove pan bottom. Peel off parchment. (Can be prepared 1 day ahead. Wrap

cake in plastic and chill.)

3.10 Syrup 2/3 cup sugar

5 tablespoons water

5 tablespoons Irish whiskey

Combine sugar and water in small saucepan. Stir over low heat until sugar

dissolves. Increase heat and bring to boil. Remove from heat. Mix in whiskey.

Cool. (Can be prepared 1 day ahead. Cover and let stand at room temperature.)

Assembly

Bands 2 14 1/2 x 3-inch waxed paper

strips

4 ounces semisweet chocolate, chopped

1 tablespoon plus 1 teaspoon solid vegetable shortening

Line large basket sheet with foil and set aside. Place another large sheet of

foil on work surface; top with waxed paper strips, spacing apart. Stir chopped

semisweet chocolate and vegetable shortening in heavy, small saucepan over low

heat until melted and smooth. Pour half of melted chocolate down center of each

waxed paper strip.

Using metal icing spatula, spread chocolate to cover strips evenly and

completely, allowing some chocolate to extend beyond edges of paper strips.

Using fingertips, lift strips and place on clean foil-lined baking sheet.

Refrigerate just until chocolate begins to set but is still very flexible,

about 2 minutes.

Remove chocolate bands from refrigerator. Using fingertips lift 1 band from

foil. With chocolate side next to cake, place band around side of cake; press

gently to adhere (band will be taller than cake). Repeat with second chocolate

band, pressing onto uncovered side of cake so that ends of chocolate bands just

meet (if ends overlap, use scissors to trim any excess paper and chocolate).

Refrigerate until chocolate sets, about 5 minutes. Gently peel off paper.

Refrigerate cake.

Chocolate Curls

12 1-ounce squares semisweet baking chocolate

Powdered sugar

Line baking sheet with foil. Unwrap 1 square of chocolate. Place chocolate on

its paper wrapper in microwave. Cook on High just until chocolate begins to

soften slightly, about 1 minute (time will vary depending on power of

microwave). Turn chocolate square onto 1 side and hold in hand. Working over

foil-lined sheet, pull vegetable peeler along sides of chocolate, allowing

chocolate curls to fall gently onto foil. Form as many curls as possible.

Repeat process with remaining chocolate squares. Place curls decoratively atop

cake, mounding slightly. (Can be prepared 1 day ahead. Refrigerate cake.) Sift

powdered sugar over chocolate curls before serving cake.

CONCLUSION

https://en.wikipedia.org

De Paor, Liam, Saint Patrick's World: The

Christian Culture of

Moran, Patrick Francis Cardinal (1913). "St.

Patrick". Catholic Encyclopedia.

Duffy, Se n (ed.), Atlas of

Irish History. Gill and Macmillan,

|