ALTE DOCUMENTE

|

|||

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT...........................page 2

CHAPTER 1

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND.....................page3

QUEEN

CHAPTER 2

POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC REFORMS.......... ..... ...... ..............page6

The Corn Laws

Chartism

The Great Exhibition of 1851

The Reform Acts

CHAPTER 3

ART AND DESIGN.........................page15

Gardens and Gardening

The Gothic Revival

The Railways

CHAPTER 4

SOCIAL ASPECTS.........................page23

Child Labour

Social Classes

The Married Woman

CHAPTER 5

LATE VICTORIAN

CONCLUSIONS..........................page29

BIBLIOGRAPHY...........................page30

ABSTRACT

The

Victorian age was an age where many changes occurred socially, economically,

and industrially. English literature was also something that was beginning to

be developed. Historically, it began when Queen

The Victorian years also brought with them the increasing efforts to achieve political, social, and economic reforms that would change the structure of the country to meet the changes created by industry. The several Reform Acts that became active throughout the years contributed very much to the

CHAPTER 1

The Victorian Age, as the decades

between 1830 and 1880 have been coined, is indebted for the name appropriation

to Queen Victoria, who ruled the

QUEEN

Warmhearted and

lively,

Queen

In the early part of

her reign, she was influenced by two men: her first Prime Minister, Lord

Melbourne, and her husband,

Albert took an active

interest in the arts, science, trade and industry; the project for which he is

best remembered was the Great Exhibition of 1851, the profits from which helped

to establish the South Kensington museums complex in

Her marriage to

Until the late 1860s she

rarely appeared in public; although she never neglected her official

Correspondence, and continued to give audiences to her ministers and official

visitors, she was reluctant to resume a full public life. She was persuaded to

open Parliament in person in 1866 and 1867, but she was widely criticised for

living in seclusion and quite a strong republican movement developed. Seven

attempts were made on

In her later years, she

almost became the symbol of the

Despite her advanced

age,

She was buried at

CHAPTER 2

POLITICAL AND ECONIMIC REFORMS

The Corn Laws (which

refer to grain of all kinds) were a series of deeds enacted between 1815 and

1846 which kept corn prices at a high level. This measure was intended to

protect English farmers from cheap foreign imports of grain following the end

of the Napoleonic Wars. During the Napoleonic Wars, the British blockaded the

European continent, hoping to isolate the Napoleonic Empire and bring economic

hardship to the French. One result of this blockade was that goods within the

When the wars ended in 1815 the first

of the Corn Laws was introduced. This law stated that no foreign corn would be

allowed into

The artificially high corn prices encouraged by the Corn Laws meant that the urban working class had to spend the bulk of their income on corn just to survive. Since they had no income left over for other purchases, they could not afford manufactured goods. So manufacturers suffered, and had to lay off workers. These workers had difficulty in finding employment, so the economic spiral worsened for everyone involved. The first major reform of the Corn Laws took place during the ministry of the Duke of Wellington in 1828. The price of corn was no longer fixed, but tied to a sliding scale that allowed foreign grain to be imported freely when domestic grain sold at 73 shillings per quarter or above, and at increasing tariffs the further the domestic price dropped below 73 shillings. The effect of this reform was negligible .Several groups arose during the early and mid 1800s to fight for repeal of the Corn Laws amid other social reforms. Most prominent among these movements were the Chartists and the Anti-Corn Law League (ACLL). The ACLL began in 1836 as the Anti Corn Law Association, and in 1839 adopted its more familiar name. Despite its social reform agenda, the league drew its members largely from the middle-class, merchants and manufacturers. Their aim was to loosen the restrictions on trade generally, so that they could sell more goods both at home and around the world. After constant agitation, the ACLL was successful, and in 1846 the government under Sir Robert Peel was persuaded to repeal the Corn Laws.

The Chartist

Demonstration on Kennington Common in 1848

The Chartist Movement had at its core the so-called "People's Charter" of 1838. This document, created for the London Working Men's Association, was primarily the work of William Lovett. The charter was a public petition aimed at redressing omissions from the electoral Reform Act of 1832. It quickly became a rallying point for working class agitators for social reform, who saw in it a cure-all for all sorts of social ills. For these supporters the People's Charter was the first step towards a social and economic utopia. In demanding so much the supporters of the charter probably ensured its downfall, for the number of demands probably diluted support for any single demand.

The People's Charter outlined 6 major demands for reform. These were: 1. Institution of a secret ballot; 2. General elections be held annually; 3. Members of Parliament not be required to own property; 4. MPs be paid a salary; 5. Electoral districts of equal size; 6. Universal male suffrage

The first gathering

of Chartist delegates gathered in

The Convention did adopt the motto "peaceably if we may, forcibly if we must", which may have frightened of those more moderate middle-class members who might have been persuaded to support their cause. Agitation continued throughout the spring of 1839, and government troops were used to ensure order in some areas of the country, notably the north.

Proponents of the charter gathered over 1,25 million signatures in support of their aims. They presented the charter and the signatures to the Parliament when it gathered in July, 1839. Though supported by future Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, the charter was rejected by the House of Commons by a vote of 235 to 46. In the wake of this defeat in the Commons, the National Convention lost its importance and finally dissolved itself in September.

With the national leadership of the

Movement no longer effective, local reformers took charge. The government had

many leaders of the movement arrested or detained. There were outbreaks of

violence in several regions, notably at

The suppression of the Chartists drew further attention to their cause, but the movement in general failed to cross class lines and gain the necessary support among members of the ruling aristocracy and landed gentry. The Chartists attempted to submit their petition to Parliament twice more, in 1842, when they claimed to have gathered over 31 million signatures of support, and for a final time in 1848. After this final failure the movement died out.

The aims of the Chartists may seem mild and eminently sensible to modern readers. But to the government of Victorian England they represented a potential for upheaval and overthrow of social institutions and entrenched authority. The violent turmoil of the French Revolution was still fresh in the minds of many in positions of authority. Rather than being swayed by the sensibilities of the Chartist's demands, they reacted in fear at the possibility of violent overthrow of society - and their own positions.

Chartism failed for a

number of reasons; most obviously, it failed to gather support in Parliament -

not surprising when considering the threat it posed to the self-interest of

those in power. Equally important, it failed to gather support from the

middle-classes. The demands of Chartism were too radical for many of the middle-classes,

who were comfortable enough with the status quo. The repeal of the Corn Laws

helped improve the economic climate of

Although the Chartist Movement failed to directly achieve its aims, a good case can be made that the movement itself was not a failure at all, but a powerful force that resulted in an increased awareness of social issues and created a framework for future working-class organizations. Many of the demands of the Chartists were eventually answered in the electoral reform bills of 1864 and 1867. It also seems likely that the agitation for reform that the Chartist Movement helped bring to the forefront of British society was responsible for the repeal of the Corn Laws and other social reforms.

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations was the first international exhibition of manufactured goods, and it had an incalculable effect on the course of art and design throughout the Victorian Age and beyond. It was modelled on successful French national exhibitions, but it was the first to open its doors to the world.

The

Exhibitions chief proponent and cheerleader was

Then

another plan surfaced, by Joseph Paxton. Initially the Commission rejected

Paxton's plan, but he took out newspaper ads to raise public support, and the Commissioners

were forced to bow to public pressure. Paxton's innovative design called for a

glass and steel structure, essentially a giant greenhouse, made of identical,

interchangeable pieces, thus lowering materials cost considerably. Paxton's

design was adopted, with the addition of a dome to allow space for some very

tall trees in

Rival architects claimed that the building was unsafe, and would collapse from the resonance set up by the feet of large crowds. So an experiment was set up. A model structure was built, and workmen walked back and forth in time and then haphazardly. Then they jumped up in the air together. No problem. As a final test, army troops were called in to march about. The test building passed the trial, so work proceeded on the real thing.

There are some quick facts and figures

about Paxton's amazing creation: The main

building was 1848 feet long and 408 wide, enclosing 772,784 square feet (19

acres), an area six times that of

Amazingly,

the building, dubbed the "

THE FIRST REFORM ACT (1832)

Between 1770 and

1830, the Tories were the

dominant force in the House of Commons.

The Tories were strongly opposed to increasing the number of people who

could vote. However, in November, 1830, Earl Grey, a Whig, became

Prime Minister. Grey explained to William IV that

he wanted to introduce proposals that would get rid of some of the rotten boroughs.

Grey also planned to give

In April 1831 Grey asked William IV to dissolve

the Parliament so that the Whigs could secure a larger majority in the House of Commons.

Grey explained this would help his government to carry their proposals for

parliamentary reform. William agreed to Grey's request and after making his

speech in the House of Lords,

walked back through cheering crowds until they all arrived at the famous

After Lord Grey's election

victory, he tried again to introduce parliamentary reform. On

On

Lord Grey's government resigned and William IV now asked

the leader of the Tories, the Duke of Wellington,

to form a new government.

When the Duke of Wellington

failed to recruit other significant figures into his cabinet, William was

forced to ask Grey to return to office. In his attempts to frustrate the will

of the electorate, William IV lost the

popularity he had enjoyed during the first part of his reign. Once again Lord Grey asked the king to create a large

number of new Whig peers. William

agreed that he would do this and when the Lords heard the news, they agreed to

pass the Act.

Many people were disappointed

with the 1832 Reform Bill. Voting in the boroughs was restricted to men who

occupied homes with an annual value of £10. There were also property

qualifications for people living in rural areas. As a result, only one in seven

adult males had the vote. Nor were the constituencies of equal size. Whereas 35

constituencies had less than 300 electors,

THE SECOND REFORM ACT (1867)

Late in March 1860,

Lord John Russell

attempted to introduce a new Parliamentary Reform Act that would reduce the

qualification for the franchise to £10 in the counties and £6 in towns, and

effecting a redistribution of seats. Lord Palmerston,

the prime minister, didn't agree with the parliamentary reform, and as a consequence to his lack of

support, the measure did not become law.

On the death of Palmerston in July

1865, Earl Russell (he

had been raised to the peerage in July 1861) became prime minister. Russell,

with the once again tried to persuade Parliament to accept the reforms that had

been proposed in 1860. The measure received little support in Parliament and

was not passed before Russell's resignation in June 1866. William Gladstone,

the new leader of the Liberal Party, made

it clear that like Earl Russell, he

was also in favour of increasing the number of people who could vote.

Although the Conservative Party

had opposed previous attempts to introduce parliamentary reform, Lord Derby's

new government were now sympathetic to the idea. The Conservatives knew that if

the Liberals returned to power,

The 1867 Reform Act gave the

vote to every male adult householder living in a borough constituency. Male

lodgers paying £10 for unfurnished rooms were also granted the vote. This gave

the vote to about 1,500,000 men which was quite remarkable for that period.

The Reform Act also dealt with

constituencies and boroughs with less than 10,000 inhabitants lost one of their

MPs. The forty-five seats left available were distributed by: giving fifteen to

towns which had never had an MP; giving one extra seat to some larger towns - Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham and Leeds; creating a seat for the University

of London; giving twenty-five seats to counties whose population had increased

since 1832.

THE THIRD REFORM ACT (1884)

The 1867 Reform Act had

granted the vote to working class males in the towns but not in the counties. William Gladstone

and most members of the Liberal Party

argued that people living in towns and in rural areas should have equal rights.

Lord Salisbury,

leader of the Conservative Party,

opposed any increase in the number of people who could vote in parliamentary

elections.

In 1884

The Victorian age, the age of industrial revolution and squalid city slums, was also the age of a popular explosion of interest in that most British of occupations, gardening. And not just as a private pastime. For the first time, a concerted effort was made by authorities to provide extensive public gardens. There was a reason for this benevolent behaviour by the well-to-do. They believed that gardens would decrease drunkenness and improve the manners of the lower classes. Intellectuals and the upper classes also encouraged gardening as means of decreasing social unrest.

In 1840 the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew passed from crown control to the government, which meant a transfer from enthusiastic amateurs to professional gardeners.

|

| ||

|

The

Palm House at |

The expanding

Inevitably, this passion for

exotic plants created a reaction in favour of traditional British plants and

garden forms, particularly the parsonage, or vicarage garden. Strangely, the

number of parsons who have had a strong influence on British garden history is

quite high. The vicarage garden was a showpiece of 1-3 acres, planted, not with

colourful exotics, but with a homogenous mix of traditional plants, such as

wisteria.

The most influential gardener

of late Victorian times was William Robinson, author of The English Flower

Garden, perhaps the most influential work in British garden history.

Robinson, and later Gertrude Jekyll, emphasized a natural look, with creepers

and ramblers, hardy shrubs, roses under planted, herbaceous plants and bulbs.

Two later examples of this natural style can be seen at Hidcote

and Sissinghurst.

Another Victorian garden

phenomenon was the

In reaction to the classical style of the previous century, the Victorian age saw a return to traditional British styles in building, Tudor and mock-Gothic being the most popular. The Gothic Revival, as it was termed, was part spiritual movement, part recoil from the mass produced monotony of the Industrial Revolution. It was a romantic yearning for the traditional, comforting past. The Gothic Revival was led by John Ruskin, who, though not himself an architect, had huge influence as a successful writer and philosopher.

Most popular architectural styles were

throwbacks; Tudor, medieval, Italianate. Houses were often large, and terribly

inconvenient to live in. The early Victorians had a predilection for overly elaborate details and

decoration. Some examples of large Victorian houses are

Most popular architectural styles were

throwbacks; Tudor, medieval, Italianate. Houses were often large, and terribly

inconvenient to live in. The early Victorians had a predilection for overly elaborate details and

decoration. Some examples of large Victorian houses are

In late Victorian times the pendulum,

predictably, swung to the other extreme and the style was simpler, using

traditional vernacular (folk) models such as the English farmhouse. This period

is typified by the work of Norman Shaw at 'Wispers' Midhurst, (S u).

u).

(

Not just styles changed. The

Industrial Revolution made possible the use of new materials such as iron

and glass. The best example of the use of these new materials was the

The cheap, mass-produced (and artistically inferior) building and decorating materials then available horrified them. Morris himself, through his Morris and Co., designed furniture, textiles, wallpaper, decorative glass, and murals. Many of Morris' designs are still popular today.

The term "Gothic Revival"

(sometimes called Victorian Gothic) usually refers to the period of mock-Gothic

architecture practiced in the second half of the 19th century. That time frame

can be a little deceiving, however, for the Gothic style never really died in

Christopher

Wren, the master of classical style, for example, added Gothic

elements to several of his

|

|

|

A Gothic Revival church |

In the late 18th century, running in parallel, as it were, with raging classicism, was a school of romanticized Gothic architecture, popularized by Batty Langley's pattern books of medieval details. This medieval style was most common in domestic building, where the classical style overwhelmingly prevailed in public buildings.

One of the prime movers

of a new interest in Gothic style was Horace Walpole.

|

|

|

Gothic Revival cottage |

James Wyatt was the most prominent

18th century architect employing Gothic style in many of his buildings. His

The

as with

as with King's College

|

|

|

|

Gothic window |

It is really only after 1840 the

Gothic Revival began to gather steam, and when it did the prime movers were not

architects at all, but philosophers and social critics. This is the really

curious aspect of the Victorian Gothic revival; it intertwined with deep moral

and philosophical ideals in a way that may seem hard to comprehend in today's

world. Men like A.W. Pugin

and writer John Ruskin (The Seven Lamps of Architecture, 1849) sincerely

believed that the Middle Ages was a watershed in human achievement and that

Gothic architecture represented the perfect marriage of spiritual and artistic

values. Ruskin allied himself with the

Pre-Raphaelites and vocally advocated a return to the values of craftsmanship,

artistic, and spiritual beauty in architecture and the arts in general. Ruskin

and his brethren declared that only those materials which had been available

for use in the Middle Ages should be employed in Gothic Revival buildings. Even

more narrow-minded than Ruskin were followers of the "ecclesiological

movement", which began in the universities of

|

|

|

|

But all this theory needed some

practical buildings to illustrate the ideals. The greatest example of authentic

Gothic Revival is the

The period from

1855-1885 is known as High

Victorian Gothic. In this period architects like William Butterfield

(Keble College Chapel,

High Victorian Gothic was applied to a dizzying variety of architectural projects, from hotels to railroad stations, schools to civic centres. Despite the strident voice of the Ecclesiological Society, buildings were not limited to the decorated period style, but embraced Early English, Perpendicular, and even Romanesque styles.

The Gothic Revivalists was very successful at the time because the Victorian Gothic style is easy to pick out from the original medieval. One of the reasons for this was a lack of trained craftsmen to carry out the necessary work. Original medieval building was time-consuming and labour-intensive.

The Albert Memorial

Yet there was a large pool of labourer's skilled in the necessary techniques; techniques which were handed down through the generations that it might take to finish a large architectural project

Victorian Gothic builders lacked that pool of skilled labourers to draw upon, so they were eventually forced to evolve methods of mass-producing decorative elements. These mass-produced touches, no matter how well made, were too polished, too perfect, and lacked the organic roughness of original medieval work.

There were railways of a single sort

before the 19th century in

unsuccessful for

transport, but the die was cast. Just a few years later George Stephenson's

Rocket became the first steam

locomotive practical to use for pulling rolling stock (train cars).

Stephenson applied the new technology to his Stockton and Darlington

Railway in1825, although in those early years horses still did some of

the work.

In 1804 Richard Trevithick

first harnessed a steam engine to a wagon. His engine was

The first truly

successful steam railway was the Liverpool and Manchester Railway

(1830). The L&M sparked a feverish boom in railway building that lasted

twenty years. By 1854 every town of any size in

One of the major problems of these early boom years was the lack of standardization (the same difficulty encountered by canal builders earlier). There were at least 5 different gauges (the distance between the rails) in use in the 1840's. This meant that trains made for one line could not use rails on another line, so goods would have to be unloaded and transferred to a new train of the proper gauge. This problem was not completely solved until the 1890's.

Rail was the most popular means of transport for goods and people throughout the Victorian era and well into the 20th century. In a sense, rail set the tone for 19th century "progress" and made possible the entrepreneurial successes and excesses of the Industrial Revolution. Some prominent Victorian railway stations are still in use, notably Paddington (the building, not the bear of the same name), St. Pancras, and York. Many rail lines that fell into disuse in the 20th century are now resurrected

CHAPTER 4

SOCIAL ASPECTS

The social classes of

Rich families

Rich families

Poor families

Poor families

There continued to be a large and generally disgruntled working class, wanting and slowly getting reform and change.

Conditions of the working class were still bad, though, through the century, three reform bills gradually gave the vote to most males over the age of twenty-one. Contrasting to that was the horrible reality of child labour which persisted throughout the period. When a bill was passed stipulating that children under nine could not work in the textile industry, this did not apply to other industries, nor did it in any way curb rampant teenaged prostitution.

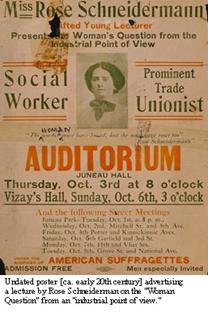

The social changes during

the Victorian age lead to questions about the role of women in society. This

societal question was popularly called "The Woman Question." The

extension of suffrage to a wider group of males in 1832 and 1867 made people

wonder when  These conditions and the new roles that these women played within society

questioned the traditional roles that women were to play at this time. The voice

of the middle class women also challenged time. The voice of the middle class

women also challenged this expected behaviour.

These conditions and the new roles that these women played within society

questioned the traditional roles that women were to play at this time. The voice

of the middle class women also challenged time. The voice of the middle class

women also challenged this expected behaviour.

women would receive equal treatment. Women in

Many factory workers were children.

They worked long hours and were often treated badly by the supervisors or

overseers. Sometimes the children started work as young as four or five years

old. Children often worked long and grueling hours in factories and had to

carry out some hazardous jobs. In match factories children were employed to dip

matches into a chemical called phosphorous. This phosphorous could cause their

teeth to rot and some died from the effect of breathing it into their lungs.

While thousands of children worked down the mine, thousands of others worked in

the cotton mills. The mill owners often took in orphans to their workhouses;

they lived at the mill and were worked as hard as possible. They spent most of

their working hours at the machines with little time for fresh air or exercise.

Even part of Sunday was spent cleaning machines. There were some serious

accidents. For instance, some children were scalped when their hair was caught

in the machine, hands were crushed and some children were killed when they went

to sleep, and because they were so tired, fell into the machine.

The degradation of the married woman in the Victorian era existed not only in that she was stripped of all her legal rights but also that no obligations were placed in her realm. Upon marriage, Victorian brides relinquished all rights to property and personal wealth to their husbands. Women were, under the law, "legally incompetent and irresponsible."

A married woman was entitled to no legal recourse in any matter, unless it was sponsored and endorsed by her husband. Helpless in the eyes of civil authority, the married woman was in the same category with "criminals, lunatics, and minors". Eighteenth-century English jurist, William Blackstone curtly described her legal status, "in law a husband and wife are one person, and the husband is that person". The Victorian woman was her husband's chattel. She was completely dependent upon him and subject to him. She had no right to sue for divorce or to the custody of her children should the couple separate. She could not make a will or keep her earnings. Her area of expertise, her sphere, was in the home as mother, homemaker and devoted domestic. Clear and distinct gender boundaries were drawn: Men were ". . . competitive, assertive . . . and materialistic." Women were "pious, pure, gentle . . . and sacrificing" No greater degradation took place in the Victorian woman's life than in the bedroom.

The Victorian woman had no right to her own body, as she was not permitted to refuse conjugal duties. She was believed to be asexual: "The majority of women, happily for them, are not much troubled with sexual feeling of any kind". The inference is, if the husband did not demand the fulfilment of his marital rights, sex would not exist in marriage. Sexual relations within Victorian marriage were unilaterally based on men and male needs.

Neither

a woman's desire, nor her consent was at issue. The ideal Victorian woman was

pious, pure, and above all submissive. The question of her consent was rarely a

matter for concern. A

The dress of the early Victorian era was similar to the Georgian age. Women wore corsets, balloonish sleeves and crinolines in the middle 1840's. The crinoline thrived, and expanded during the 50's and 60's, and into the 70's, until, at last, it gave way to the bustle. The bustle held its own until the 1890's, and became much smaller, going out altogether by the dawning of the twentieth century. For men, following Beau Brummell's example, stove-pipe pants were the fashion at the beginning of the century. Their ties, known then as cravats, and the various ways they might be tied could change, the styles of shirts, jackets, and hats also, but trousers have remained. Throughout the century, it was stylish for men to wear facial hair of all sizes and descriptions. The clean shaven look of the Regency was out, and moustaches, mutton-chop sideburns, Piccadilly Weepers, full beards, and Van Dykes (worn by Napoleon III) were the order of the day.

|

| |

|

Disraeli |

This era could be

subtitled 'The Gladstone and Disraeli Show' for the two politicians who

dominated it. The two men, Gladstone and Disraeli, could not have been more

dissimilar.

This was

also the age of the 'Irish Question', the question being whether or not the

Irish should be allowed to rule themselves.

.In this age before TV's, computers, and

Nintendo, the most common form of entertainment was reading aloud. Writers like

Dickens, Tennyson, and Trollope were widely read and discussed. The advent of

universal compulsory education after 1870 meant that there was now a much

larger audience for literature. Disraeli himself, when he was not locking horns

with

Much of the attention of the

country was focused abroad during this era. In 1876

On the home front the Industrial Revolution

gathered steam, and accelerated the migration of the population from country to

city. The result of this movement was the development of horrifying slums and

cramped row housing in the overcrowded cities. By 1900 80% of the population

lived in cities. These cities were 'organized' into geographical zones based on

social class - the poor in the inner city, with the more fortunate living

further away from the city core. This was made possible by the development of

suburban rail transit. Some suburban rail companies were required by law to

provide cheap trains for workers to travel into the city centre.

The growth of rail transit

also gave birth to that Victorian mainstay, the seaside resort. As the

Industrial Revolution progressed, working hours decreased, and the introduction

of Bank Holidays meant that workers had the time to take trips away from the

cities to the seaside. The seaside resorts introduced the amusement pier to

entertain visitors. Some of the more famous resorts were at Blackpoll and

The Industrial Revolution also

meant that the balance of power shifted from the aristocracy, whose position

and wealth was based on land, to the newly rich business leaders. The new

aristocracy became one of wealth, not land, although titles, then as now,

remained socially important in British society

CONCLUSIONS

In

conclusion, the Victorian century was an era of change and confusion.

GENERAL BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ciugureanu, Adina, Victorian Selves (A Study in the Literature

Of the Victorian Age),

Lerner, Laurence, The Context of The Victorian Period,

Vicius, Martha, Suffer and Be Still (Women in the Victorian

Age),

Williams, Raymond, Arhitecture and Style 1780-1950, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1978

|