UNIVERSITATEA BUCURESTI, FACULTATEA DE LIMBI SI LITERATURI STRAINE

LUCRARE METODICO-STIINTIFICA PENTRU OBTINEREA GRADULUI DIDACTIC I

Teaching the Future to Romanian Learners of English

(Upper-Intermediate & Advanced Levels)

Contents:

I INTRODUCTION – the reason why I chose this particular subject for my paper.

II A THEORETICAL APPROACH OF THE SUBJECT

A BRIEF HISTORY OF FUTURE TENSES

II.1 Old English

II.2 Middle English

II.3 Early Modern English (from the 16th up to the 20th century)

III MEANS OF EXPRESSING FUTURITY IN PRESENT-DAY ENGLISH

III.1 Introduction. A description of the concepts of time /tense.

III.2 The Romanian view of futurity

III.3The English paradigm

III.4 Alternative Devices for Expressing Futurity

III.5 Overall description of the future forms, in point of meanings and uses

III.6 Futurity in complex sentences

IV METHODS, STRATEGIES AND TECHNIQUES IN LANGUAGE LEARNING/ TEACHING

IV.1 What does “learning” mean? Introduction

IV.2 A brief survey of the trends before the 20th century

IV.3 20th Century Approaches to Language Teaching

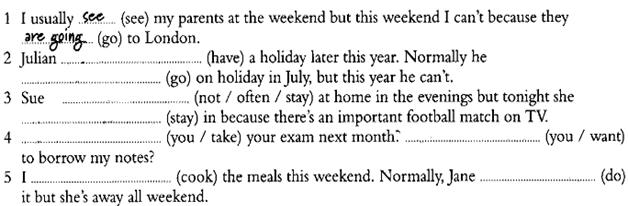

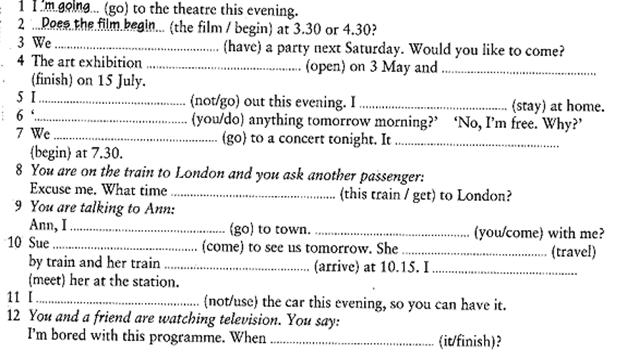

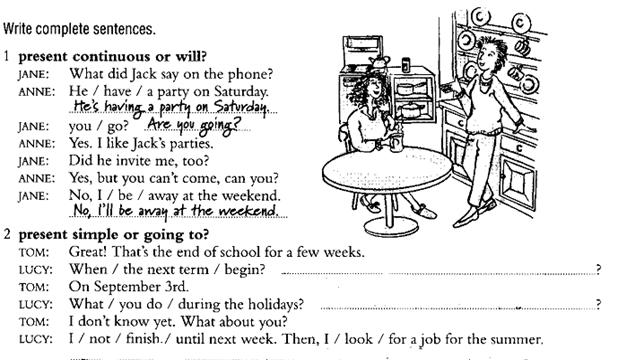

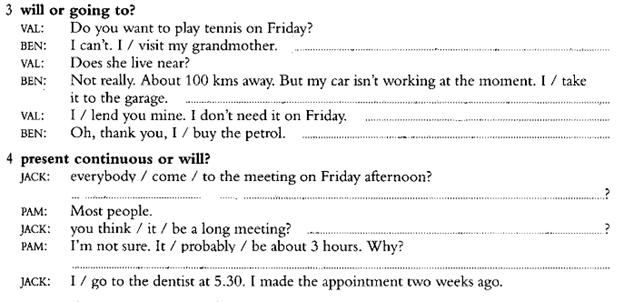

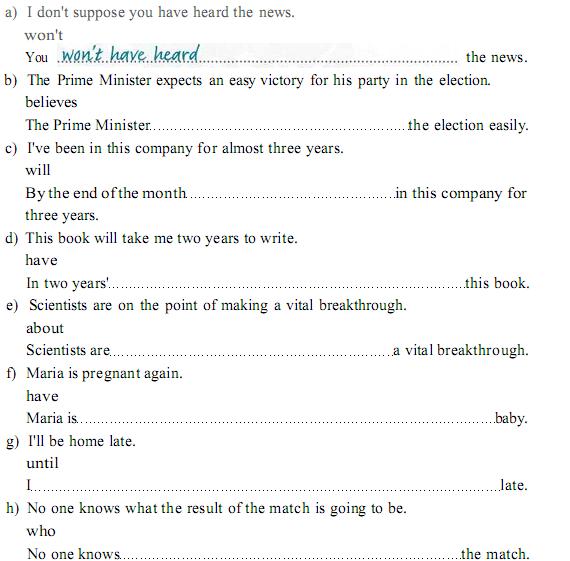

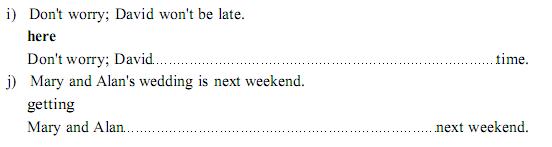

V ACTIVITIES DESIGNED TO PRACTISE FUTURITY

VI CONCLUSIONS

VII REFERENCE (bibliography and webliography)

I INTRODUCTION

‘When I use a word,’ Humpty Dumpty said in rather a

scornful tone, ‘it means just what I choose it to mean

– neither more nor less.’

‘The question is,’ said

words mean so different things.’

(Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking Glass)

The aim of this paper is to give a helpful account of lexical and grammatical devices with future reference, both in English and Romanian, in a contrastive and functional approach, so that the similarities and the differences - in perceiving and relating to the concept of time and linguistically rendering them in the two languages - could be properly coped with by the Romanians when using English as a communicative tool (Ch. II and III).

First of all, the assumption that Romanian learners of English could experience difficulties in understanding and producing utterances with future time reference is obviously true, given 1) the general opinion that natural languages are immensely complicated structures, embodying meaning(s) in highly intricate manners which are different from one language to another. This is also my personal finding during my experience as a teacher, which is 2) the second compelling reason why I chose to tackle the concept of futurity functionally; the Romanian speakers of English, (students of any level), encountered difficulties in understanding to which extent a certain modal-auxiliary is either a grammatical instrument (auxiliary) or a modal verb with specific status and function in the context (e.g. WILL, SHALL, WOULD, SHOULD), especially in secondary clauses (conditional and temporal ones). Or, they find it difficult to go deeper into their mother tongue and see that the same tense, for instance, Future/Present Indicative (Viitor/Prezent Indicativ) can convey extra meanings, apart from the mere anchorage at a certain moment on the time axis. (Not only does this tense refer to activities/states in the future, but it also adds an extra-quantity of meaning, such as speaker’s attitude, promises, threats, which are not always formally/overtly instantiated, but very frequently inferred). This is precisely the point where Romanian learners of English get lost in the multitude of linguistic means of relating to the future concept in English (and therefore become inefficient in expressing whatever they need to), as the Romanian language is not so much focused on the semantics of moods and tenses, not to say on function, as English is, the result being a reduced number of grammatical devices involved in producing meaning and function. The following examples give an account of such differences:

1)Cerul e intunecat. Va ploua. vs

2)Te voi ajuta/Te ajut eu sa scrii eseul.

in which 1) is a future assumption based on present evidence, the English counterpart being ‘Going to’ Future,

1)The sky is dark with clouds. It is going to rain.

and 2) is a promise, simple future being used here exclusively,

2)I’ll help you to write your essay.

There is, however, a mention to be made when dealing with futurity, linguistically speaking: not only does this paper intend to describe English and Romanian future tenses, it also takes into account other grammatical or lexical ways with future reference – instances when modality adds to this and, even a bit more complicated, secondary clauses on which the sequence of tenses constraints are imposed; nor can it draw a clear line between the auxiliary values of words like WILL/SHALL, WOULD/SHOULD and their modal content, as there are very few contexts in which they are either one or the other (infra II1).

e.g. He’ll probably finish this project.

I will invite you to the next concert. (Is this volition - modal content, or a promise, a certain future activity, etc., therefore a future tense? If the first half of the question has a positive answer, then WILL is a modal verb, conveying ‘volition’, with present reference, the Romanian variant being: ‘Doresc/Vreau sa te invit la urmatorul concert.’ If, on the contrary, this is a future tense, then we are dealing with a wide range of extra-meanings not literally rendered, but it is a case of time/discourse deixis, that is the sentence gains the extra-meaning(s) from the context:

e.g.i Since I have two tickets and no one else likes classical music more than you, I’ll invite you to the next concert. [certainty]

ii Last time you got upset that I didn’t count you in, but I will invite you to the next concert. [a promise]

iii As I don’t have anyone else to assist me with the review, and nobody seems to offer to go, I will invite you to the concert. [decision]

iv If you don’t stop picking on me about not taking you to the last concert, which was awful, I’ll invite you to the next concert. You’ll have enough of it! [a kind of threat]

The time reference is clear, but the full meaning or the semantic value is clear only given a larger context as a background for decoding the utterance. Again, this is not only a problem of structure or grammar, but the attempt of setting the meaning(s) goes into the function/semantics of language, (that is, pragmatics), since a certain pattern does not necessarily and unambiguously convey a certain meaning in a smaller context, as seen in the example above, but in a larger one. Particularly this gives Romanian learners of English difficulties in translating/writing simple or complex texts or in using English in conversation. In order to picture a clearer image of the lexical or grammatical devices that have future time reference, starting with their functional role, a full account of these will be given, together with their Romanian counterparts, and how they appear in usage (in both written and spoken English) (Ch. III).

Secondly, this paper looks at various teaching models that influenced current teaching practice (Ch. IV). There will be short descriptions of five most frequently used (in the past or recent years) learning techniques: Grammar-translation, Audio-lingualism, PPP (Presentation, Practice and Production), Task-Based Learning and Communicative Language Teaching. The subsequent part of this paper (Ch. IV) will deal with examples of class activities, designed from the perspective of the above mentioned learning methods/techniques, covering all skills: writing, reading, listening and speaking.

The last part of the paper will contain lesson plans on the subject, the conclusions I reached while researching for and writing this paper, and bibliographical and webliographical references.

II A THEORETICAL APPROACH OF THE CONCEPT

A BRIEF HISTORY OF LINGUISTIC DEVICES RENDERING FUTU-RITY

‘Historical development proceeds not by stages,

but by overlaps.’ (Wrightson 2002: 24)

INTRODUCTION: PERIODS OF THE ENGISH LANGUAGE

As with every natural language, English has been greatly altered during the centuries. Research in this field divided its history into three major periods:

Ø Old English (before c. 1100)

Ø Middle English (c.1100-1500)

Ø Modern English (after c. 1500)

Many historians divide the Modern English period into Early and Late Modern English,

with a dividing line set around 1700. In An Introduction to Early Modern English, Terttu Nevalainen, a professor of History of English in the Universities of Helsinki and Cambridge, gives a fragment in the Bible (Genesis 1:3), in three translations, each dating different centuries, to sustain the legitimacy of dividing English into the three periods of evolution.[1]

II.1 THE OLD ENGLISH PERIOD (the Anglo-Saxon)

The Anglo-Saxon, like all the Teutonic languages, had but two tenses: the present and the preterite. The uses of these two tenses are far more limited now than it was before the 11th century. However, they are still employed today bearing future reference in certain linguistic contexts. Utterances like ‘I’m visiting my grandma next weekend’ or ‘Tomorrow is Monday,’ and many others, are common in present speech as well as in writers’ works.

It is to be noted that neither willan ‘will’, nor sæeal ‘shall’ has the meaning of futurity as they have today, except in the occasional, and rather literal, translation of the Latin future. E.g.:

These examples are interpreted as expressing necessity with future implications, in much the same way the present-day modal ‘shall’ does. Yet, in reported speech, there are examples which do not look as if they are a copy of the Latin language and in which sæeolde “should” represents a form of the Future-in-the-past.[2]

Simultaneously, the two forms of what appear today as auxiliaries of future tenses ‘shall’, ‘will’ were employed, but carrying certain meanings and not serving as pure grammatical instruments in forming tenses as they are claimed to be doing today: ic sceal meaning ‘I am obliged to’, and ic wille meaning ‘I wish to’. The two forms have never lost their connotation of obligation and desire respectively, therefore their grammaticalisation is not complete , (in an Old English clause, therefore, such as ‘Ic wille þone hlaford ofslēan’ ‘I want to kill the lord’, wille is a lexical verb which implies volition as well as futurity but today their main function is to signal futurity or prediction, among many others, quality which they developed in the Middle English period.

II.2 THE MIDDLE ENGLISH PERIOD

Between the 11th and the end of the 15th centuries, futurity was rendered by the use of a smaller number of linguistic devices, but the partial overlapping of the grammatical and modal, thus lexical, functions of WILL/SHALL is easily perceptible even from those times then.

The verbs schal and - to a certain extent - wil (wol) were now frequently used to denote a future action, even if their meanings from OEP (Old English Period) were not lost completely - volition and obligation, respectively - (nor are they today):

E.g. ‘Ther-as the knightes weren in prisoun, of whiche I tolde yow, and

tellen shall

In some contexts, they can have a modal meaning as well, especially wil:

E.g. Our sweete Lord God of hevene wole that we comenalle to the

knowleche of Hym..

[Our sweet Lord God of heaven wishes that we all come to know-

ledge of him]

E.g. he shal first biwaylen the synnes that he has doon

[he must first bewail the sins that he has done]

However, it could be argued that they are used simply as future auxiliaries or as modal verbs exclusively, as the idea of volition or obligation implies futurity, thus, the development towards the future time auxiliary status is not a dramatic grammatical change.

Even in the literature of the time it became obvious that the two (shall/will) started developing their main function – to signal prediction, futurity:

E.g. ‘I shal myself to herbes techen yow

That shul been for youre heele and for youre preow.’,

says a character in one of Chaucer’s poems. Here, shal is singular (OE sceal) and shul is plural (OE sculon), and the meaning of the sentence is ‘I shall myself direct you to herbs that will be for your health and benefit’. The tendency of using shall for the first person and will for the second and third, when using these words as simple markers of the future, is quite recent and not universal even today: in Northern England one can often hear ‘Shall you go?’, where a Londoner will say ‘Will you go?’.

A future reference was also expressed periphrastically by ben aboute (for) to, followed by infinitive:

E.g. ‘Thou wouldest falsly ben aboute to love my lady.

along with the present tense inherited from OEP.[5]

II.3 EARLY MODERN ENGLISH (from the 16th to the 20th century)

As far as the future is concerned, the weakened meaning of shall and will was more obvious than it had been in Middle English,

E.g. ‘He that questioneth much, shall learn much.’ (Francis bacon, Essays)

E.g. ‘I will sooner have a beard grow in the palm of my hand than he shall get on his neck.’ (Shakespeare, Henry IV, part II).

Up to the beginning of the 17th century there were no differences in use between will and shall for expressing the future, the first mention to these delimitations of use and meaning being made by George Mason , who noted the supplementary volitional content of will when used in any person and the use of shall in the first person especially.

The signs of the future are shall or will, but they shouldn’t be used indiscriminately: since if you use the sign shall when will should be used, it will sound improper and it will seem as if you are speaking too audaciously: for example, you could say appropriately If I doe eate that, I shall be sicke, ‘If I eat that, I shall be sick’, instead, if you said I will be sicke, it will seem as if you willingly wish to be sick; similarly, you could say: I hope you will be my good friend, If you doe that, you shall bee beaten or chidden, ‘If you do that, you shall be beaten or chidden’, but I shall not, but you shall not chuse, ‘but you shall not choose,’ that is to say, it will not be your choice: To be short, it is not easy to give a fixed rule, therefore I refer you to usage, and in order to understand it better, we shall propose the conjugation of certain verbs.’ (Mason, G., pages 25-26)

By the end of the Early Modern English period, many of the grammatical structures and terms familiar to us had found their place in the grammars of the time. In 1653, John Wallis wrote his Grammatica Linguae Anglicanae in which he stated the rules of shall and will, according to which these two devices served to indicate the future (prediction), shall being used in the first person and will in the second and third person. [7]

A few decades later, Cooper made an even clearer distinction between shall and will, stating that shall in the first person expresses declaration, while with the other persons it conveys an order.

In the latter half of the 17th century, the construction be going to developed a special meaning indicating future time. The process is thought to have started aound 1600, but there is only one example from Shakespeare , according to Jespersen, (apud Ioana Stefanescu, English Morphology, 2nd Volume, Bucuresti, 1988, page 305). Present continuous, too, started to take on the new meaning. It is an example of grammaticalisation, a process in which lexical material becomes fixed in grammatical function. In present-day English, the former expression has grammaticalised even further, being reduced to gonna (we’re gonna be there).

E.g. Sr John Walter is going to be marryed to my Lady Stoel, wch will be very happy for him. (H.C., Anne Hatton, 1695, page 214)

During this period, will started to gain ground in the first person, while being used in parallel with shall, the appearance of the new structures (going to and be to) having little (if any) influence over the use of the two modal-auxiliaries. As for the old device employed for conveying futurity (the present tense simple), this was too still in use, when the future event contained a high degree of certainty[10]:

Nowadays, English has a wide range of ways of referring to the future, each and every one of them having not only grammatical, but semantic or functional values, as well, which will be dealt with in II2.

III MEANS OF EXPRESSING FUTURITY IN PRESENT-DAY ENGLISH

III.1 Introduction

To begin with, I am going to cite the definition given by the authors of ‘A Grammar of Contemporary English’, R. Quirk, S. Greenbaum, G. Leech and J. Svartvik, to the idea of time/tense: ‘ in abstraction from any given language, time can be thought as a line (theoretically, of infinite length) on which is located, as a continuously moving point, the present moment. Anything ahead of the present moment is in the future, and anything behind it is in the past. []

THE PRESENT MOMENT

![]()

PAST FUTURE

![]()

![]()

[now]

Figure The representation of the concept of time

This is an interpretation of past, present and future on a REFERENTIAL level. []

(page 175)

[] we distinguished past, present and future also on a SEMANTIC level. On this second level of interpretation, then, ‘present’ is the most general and unmarked category’ as a statement constructed with the present simple can be applicable to present, past and future, while the past tense has a more restricted applicability:

E.g. John spends a lot of money. (true for past, present, and future)

E.g. John spent a lot of money. (true for past only)

Like most grammarians, the authors of this grammar do not accept the future as a formal category, since, morphologically, English does not have verb inflection for such a category, but they accept the idea of ‘grammatical constructions capable of expressing the semantic category of FUTURE’. One reason for sustaining this, is the lack of inflection for such a category, the present and the past being morphologically marked (-s/-es, for the 3rd person singular, present simple and -ed, for all persons in past simple, respectively), if tenses are defined as forms of the verb.

Another reason for admitting the existence of only two tenses in English derives from the diachronic perspective of the phenomenon of futurity, in that future reference was carried out during middle English not only by the present tenses, but by the subjunctive mood, as well. This leads to the reconsideration of the concept of mood itself, as it has been perceived both in English and Romanian so far. In the recently issued (2005) Grammar of the Romanian Language, «Modurile personale (predicative) sunt ansambluri de forme verbale care se incadreaza in categoria modalizatorilor, adica a acelor expresii lingvistice care redau implicarea vorbitorului in enunt. [] In gramaticile curente, modurile verbale sunt caracterizate pe baza opozitiei real~posibil (nonreal): Indicativul exprima procese reale, conditionalul, conjunctivul, imperativul si prezumtivul redau procese posibile (nonreale). […] vorbitorul poate sa prezinte procesul ca fictiv (“contrafactual”), ca probabil (“nonfactual”) sau ca sigur (“factual”).»[13] The same work gives account of the Indicative mood as the finite mood that consists of both synthetic and analytical forms which render information about the anchorage in time of the communicated processes and about the “real”=factual content of the utterance. The certainty associated with this mood becomes debatable when referring to the future time reference utterances or the whole debate moves the matter into the modality – pragmatics – functional grammar area. To say nothing about the fallacy of the assumption that the Indicative mood satisfies the truth-cond 747c29h itional requirement/principle which any factual = ‘real’ utterance has to fulfil.

On the other hand, English linguistic studies and dictionaries define ‘mood’ as being ‘any one of the groups of forms in the conjugation of a verb that serve to show the mode or manner by which the action denoted by the verb is represented’ , or ‘different forms of the verb used according to whether a fact or hypothesis was being expressed’ , or ‘finite verb phrases .] which indicate the factual, nonfactual, or counterfactual status of the predication’.[18] The distinction is too coarse to describe the nature and functions of the moods and, implicitly, of the tenses English employs in communicating, as it will be shown below.

There is another aspect that should be mentioned: the main constructions used to express futurity, especially the so-called shall/will forms, bear various modal nuances which the other two time frames, the present and past, respectively, do not possess at all. This is due to the fact that shall and will are modal/auxiliary verbs, that is, grammatical devices, used for building specific categories (such as tense) on the one hand, and semantic units, on the other, which means that they bring extra-information to the utterance, such as the attitude of the speaker towards their discourse, generally speaking; therefore, the discussion about the future tenses and the like overpasses the limitations of grammar seen as structure only, and is better unveiled by the theory of modality and speech acts (subsequently adopted as a new linguistic branch/study, Pragmatics), via semantics, as shown in the pie chart below:

Figure The threefold approach of the linguistic sign

The arrows connecting the three wedges of the pie illustrate the interconnectedness of the three dimensions; thus, a change in any wedge will have repercussions for the other two.

The wedge having to do with form/structure refers to those overt lexical and morphological forms that show how a particular grammar structure is constructed (Marianne Celce-Murcia, Teaching English as a Second or Foreign Language, page 252).

In the semantic wedge, we deal with what a grammar structure means, both lexically and grammatically (i.e. a dictionary definition of an auxiliary or the time adverbial clause states the moment when the action in the main clause takes place, etc. respectively.) In respect of the third wedge, the definition given by Levinson in Pragmatics, 1983, p.9, is the most appropriate explanation: “the study of those relations between language and context that are grammaticalised, or encoded in the structure of a language”.

The threefold approach of the ways of expressing futurity may be ascertained by asking the following question: Why and when does a speaker/writer choose a particular grammar structure over another that could express the same meaning or accomplish the same purpose? For example, what factors in the social context might explain a paradigmatic choice such as why a speaker chooses I shall come, too., rather than I will come, too.? or Will you do as I say, please? vs. Do as I say!, in which case an interrogative form is used instead of a plain imperative? One possible answer and with great teaching efficiency can be the rearrangement of this topic so that it meets the communicative needs of any Romanian learner of English, up to the upper-intermediate and advanced levels.

As for myself, I follow Vet’s view of the matter: ‘The Simple Future is like a mood in that it expresses the speaker’s attitude towards the future eventuality. It is a future tense because it places the eventuality posterior to the speech point.’[19]

III.2 The Romanian view of futurity

As mentioned in the first chapter, Romanian looks at the present topic rather ‘shyly’, in that it gives descriptions of the grammatical categories mostly from a formal point of view, overriding the functional/pragmatic aspect which can lead to a more accurate normative work. This mention needs asserting if one is viewing the matter from the pedagogical standpoint, as I am trying to do here.

As with any dictionary of linguistic terms or grammar, the Romanian linguists (especially those who revised and issued the older Gramatica Academiei -the Academy Grammar of Romanian, 2005) define tense referring to a linear continuum on which various events, states or actions anchor. Moreover, in order to render simultaneity, and, more complicated, anteriority and posteriority, a standpoint/point of reference is designated, that is the speech time (t0), according to which processes are qualified as past, present or future:

«Tense is the grammatical category that indicates the anchorage of a process (action, event or state) in relation with the time of speech and that is instantiated under groups (sets) of verbal forms. In other words, grammatical tense gives account of the systematic correlations between verbal forms that the processes are rendered by and the communicative/speech situation. According to the interval within which the speech act occurs, the temporal semantic field is segmented into three areas: present (‘now’), past (‘so far’) and future (‘from now on’):

∞----------past----------} {---------future---------∞

Figure The semantic areas of the concept of time

The semantic areas represent the so-called Time Reference (TR) of the verbal forms.»[20]

The Romanian work cited above (and which is the leading voice concerning the Romanian grammar) refers to futurity within the Indicative mood, highlighting only a few of the wide range of possibilities of referring to processes subsequent to the moment of speaking. All forms that have such temporal reference are analytical, as their Germanic counterparts, including English and, oddly, unlike the other Romance languages that have inflectional future forms.

i) The first form with future reference described is the Proper Future (VIITORUL PROPRIU-ZIS) also named the Formal/Literary Future in an English account of the Romanian language , an analytical form formed by an affix: voi, vei, va, vom, veti, vor, (coming from a notional verb ‘a vrea’ = ‘to want’, the older ‘to will’), and the bare infinitive of the main verb. So far there is a striking resemblance in form to the English will-future, but the two languages go different ways in some points of function and usage (infra II2.3).

E.g. voi merge, vei merge, va merge, etc.

The second form employed by Romanian is an analytical form, as well, different from the previous one in point of register, as it is exclusively used either in informal/colloquial Romanian or in literary texts. This form consists of an affix - oi, ai, (ei, ii, oi), o, (a), om, ati (eti, iti, oti), or and the infinitive of the main verb.

E.g. oi merge, ai merge, o merge, om merge, etc.

Another construction used in romanian for referring to future processes is built with an affix ‘o’ and the subjunctive/conjunctive form of the verb. This variant is mostly used in colloquial Romanian.

E.g. O sa merg, o sa mergi, o sa mearga, etc.

The last variant of this tense comprises a combination of the present form of ‘a avea’ = ‘to have’ and the present subjunctive form of the main verb. This construction is very widely used both in formal and informal style.

E.g. am sa merg, ai sa mergi, are sa mearga, etc.

Most of the above mentioned forms, if not all, do not have a one-to-one relationship with the English forms, thus, the function and the particular meaning of each instantiation brings about a lexical-grammatical constraint when choosing the equivalent.

E.g. Nu stiu ce sa mai cred. Ieri a spus ca azi la ora 8 va fi aici (dar n-a

venit. (Future Indicative/ Viitor Indicativ)

[I don’t know what to think. Yesterday he said he would be here at 8

o’clock, (but he hasn’t come.) (Future-in-the-past, Indicative)

There is another special periphrastic compound, though, which expresses posteriority, as well, and which occurs in contexts with other verbs having past reference. This consists of the Indicative-imperfect form of ‘to have’ and the present conjunctive/subjunctive form of the verbs and is referred to as Viitorul in trecut (Future-in-the-past).

In referring to the content of these future time forms, the Romanian linguists identify three features: a temporal one [Posteriority towards a t0], an aspectual one [- Perfective] and a modal characteristic [+ Real]. They are deictic tenses, as they refer to processes posterior to the time of the utterance, although there are many contexts in which some future forms, such as Viitorul in trecut (Future-in-the-past) are subsequent to a past time point of reference

E.g. «Abia atunci am realizat eu ca acest cantec avea sa imi schimbe oare-

cum viata.» (As, 2003) (Viitorul in trecut, Indicativ)

«It was not until then that I realized that song was going to change my

life to some extent.» (Past form of ‘Going to’ Future, Indicative)

E.g. «Ma intrebam numai daca din ele avea sa mi se dezvaluie vreodata

ceva.» (Mateiu Caragiale, Craii de Curtea Veche) (Viitor in trecut, in-

dicativ)

«I was only wandering whether I would ever be revealed something, if

anything.» (Future-in-the-past, Indicative)

A rather rich collection of deictic time phrases are associated with any of the future tenses described above. They are considered to be a) deictic intrinsically referential expressions’ (The A.G., page 443) and contribute to the anchorage of a process on the time axis: maine, poimaine, raspoimaine, (tomorrow, the day after tomorrow, in three days’s time and their combinations, b) ’deictic relational expressions’, such as in cateva zile/clipe/minute etc, (in a few days’/minutes’/moments’ time de acum in doi/trei/zece ani (two/three/ten years from now); la pranz/noapte/vara/apusul soarelui etc. (at noon/tonight/this summer/at sunset in iarna/primavara/februarie/octombrie/2012/2016 etc (in winter/spring/February/October/2012/2016); in noaptea/primavara/luna/ vara viitoare etc. (tonight/next spring/month/summer).

Some other – dupa catva timp, dupa o zi/saptamana/trei luni, (after a while/a day/three months later), un an/secol/deceniu mai tarziu, etc., (a year/century/decade later), in acel moment/in acea clipa/zi/seara, etc., (in that moment/on that day/night) – function anaforically, as well as with past time reference tenses:

E.g. In 2004 s-a mutat to Londra. Dupa doi ani se va stabili in New York.

(Viitor, Indicativ)

[In 2004 he moved to London. Two years later, he would settle down

in New York.] (Future-in-the-past, Indicative)

vs.

In 2004 s-a mutat la Londra. Dupa un an s-a stability la New York.

(Perfect compus, Indicativ)

[In 2004 he moved to London. Two years later, he settled to New

York. (Past Simple, Indicative)

E.g. Mult mai tarziu micuta printesa avea sa afle ca ilustra bunica-poeta

nu fusese deloc fericita de casatoria nepotului ei []cu superba Ma-

ria.(As, 2003) (Viitor in trecut, Indicativ)

[Much later the little princess was to learn/would learn that her dis-

tinguished poetess-grandma wasn’t happy about her grandson’s

marriage to gorgeous Maria.] (As, 2003) (Past form of ‘be to’,

Indicative)

E.g. Va pleca in Franta in ianuarie. (Viitor I, Indicativ)

[She will/is going to leave/is leaving for France in January.]

(Will-future/‘Going to’ Future/Present Continuous, Indicative)

Vs.

E.g. A plecat in Franta in ianuarie. (Perfect compus, Indicativ)

[He left for France in January.] (Past Simple, Indicative)

In this respect, English is very much the same as Romanian. (Infra II2.3)

Another aspect that is worth mentioning when considering the temporal approach of the matter is the overlapping between the tense and other verbal functions, such as aspect, mood, etc., which leads to debates whether an example as the following refers to the future or has it an a-temporal meaning:

E.g. Intotdeauna luna se va invarti in jurul Pamantului.

The Moon will move round the Earth forever.

In both languages, the future forms refer not only to a subsequent period, but it states a general truth, which classifies its meaning as omni-temporal. For this reason linguists introduced an alternative terminology (e.g. ‘past’ vs. ’non-past’, ‘future’ vs. ’non-future’ or ‘present’ vs. ‘non-present’), to describe certain contexts where reality is described in absolute terms, the tenses losing their deictic features. Therefore, there are situations when the content of an utterance is not contextualized relative to a certain point on the time axis, but the proposition applies to any point on this axis. This again reshapes the relation between time and tenses.

Regarding the modal feature [+Real], the Romanian linguists describe the future forms introduced above as baring various modal nuances, ranging from tentativeness to absolute certainty:

Ø Uncertainty, probability:

E.g. Nu stiu daca o veni maine la scoala. (Viitor popular, Indicativ)

[I don’t know/wonder whether he’ll come to school tomorrow

(Simple Future, Indicative)

Ø Hopes, predictions whose degree of certainty is low:

E.g. Voi reveni mai tarziu (Viitor, Indicativ)

[I’ll return later.] (Simple Future, Indicative)

Ø In conditional sentence, these forms render hypothesis, possibility, in which case it overlaps with other grammatical moods (Conditional optativ, Prezumtive):

E.g. Daca il voi intalni, ii voi spune. (Viitor, Indicativ)

[If I see him, I will tell him.] (Simple Present and Simple Future, respectively, Indicative)

ii) Another form with future reference is Viitorul anterior (cosidered to be the equivalent of the English Future Perfect). It is built with the same affixes as the Proper Future, types I and II – voi (oi), vei (ai, -i, ii), vom (om), veti (ati, eti, iti, oti), vor (or), the affix fi and the participle form of the verb.

E.g. eu v(oi) fi ras, tu vei (ai, ei, -i, ii) fi ras, el va (o, a) ras, etc.

The temporal content of this verbal form is situated after the moment of speaking (t0) and before a certain limit in the future (tx), gainins two features [+ Posteriority towards t0] and [+ Anteriority towards tx]. Another two features are associated with this form [+ Perfective/Perfect] and [+ Real],

E.g. Dupa ce voi fi incheiat lucrul, ma vei lasa sa te ajut? (Viitor anterior

and Viitor propriu-zis, Indicativ)

[After I have finished my work, will you let me help you?] (Present Per-

fect and Simple Future, Indicative due to the constraints of the tense se-

quence)

In Romanian, this form (Viitor Anterior) has a bookish/pedantic character, that is why its significance is usually conveyed by Viitor Propriu-Zis or Perfect Compus, Indicativ.

Alongside the forms presented so far, Romanian makes use of the Present Indicative to refer to some processes situated after t0. This is an inflectional tense and can convey meanings belonging to the three conventional temporal segments past-present-future:

E.g. Maine plec la Sinaia. (Prezent, Indicativ)

[Tomorrow I’m leaving for Sinaia.] (Present Continuous, Indicative)

E.g. De acum incolo lucrez numai seara. (Prezent, Indicativ)

[From now on I’ll work in the evenings only.] (Simple Future, Indic-

ative)

E.g. Raman in Bucuresti pana vineri. (Prezent, Indicativ)

[I’m staying in Bucharest until Friday.] (Present Continuous, Indic-

ative)

This type of present is called ‘extended present’ and is always accompanied by relational deictic expressions such as: de acum inainte, pana la anul, deseara, la noapte, maine, etc. (from now on, until next year, tonight, tomorrow).

There is another use of the Romanian tense, the prospective present, which refer as well to a period of time situated after the moment of speaking:

E.g. Mai avem de asteptat. Trenul pleaca la 7.30. (Prezent, Indicativ)

[We have some more minutes to wait. The train leaves at 7.30.]

(Simple Present, Indicative)

E.g. Maine este ziua mamei. (Prezent, indcativ)

[Tomorrow is my mother’s birthday.] (Simple Present, Indicative)

E.g. La vara implineste 17 ani. (Prezent, Indicativ)

[Next summer she will turn 17.] (Simple Future, Indicative)

E.g. Avionul decoleaza in doua ore. (Prezent, Indicativ)

[The plane takes off in two hours’ time.] (Simple Present, Indicative)

E.g. Vin peste doua ore. (Prezent, Indicativ)

[I’m coming back in two hours.] (Present Continuous, Indicative]

The usage of the Romanian tenses pays no attention to other modal/pragmatic criteria of selection than the connotation [ Real]. Conversely, English takes into account the type of the utterance most adequate for each communicative purpose and circumstance, thus the grammatical overlapping between the two languages is a far-reaching exploit; therefore, the systematization of speech acts, (with future time reference, for our purpose), would instil a sense of order among the linguistic varieties in both languages, and especially in Romanian, as well as the correspon-dence between the two languages and, implicitly, the use of English as L2 would be a much easier endeavour.

III.3 The English paradigm

Traditionally, what is generically called the “future tenses” of the English language appears under the following form:

|

TENSE |

ACTIVE FORMS |

PASSIVE FORMS |

|

SIMPLE FUTURE |

I/We shall buy You/He/She/It/They will buy |

I/We shall be bought You/He/She/It/They will be bought |

|

FUTURE CONTINUOUS |

I/We shall be buying You/He/She/it/They will be buying |

no forms |

|

FUTURE PERFECT SIMPLE |

I/We shall have bought You/He/She/It/They will have bought |

I/We shall have been bought You/He/She/It/They will have been bought |

|

FUTURE PERFECT CONTINUOUS |

I/We shall have been buying You/He/She/It/They will have been buying |

no forms |

|

FUTURE-IN-THE-PAST SIMPLE |

I/We should buy You/He/She/It/They would buy |

I/We should be bought You/He/She/It/They would be bought |

|

FUTURE-IN-THE-PAST CONTINUOUS |

I/We should be buying You/He/She/It/They would be buying |

no forms |

The inventory shown above does not cover the great variety of communicative needs that the speaker/observer has when it comes to referring to processes situated ahead of them. Rather, a great deal of other forms/structures and lexical units serve the speaker’s purposes, tense/time being a strictly deictic category which imposes constraints in selecting one form over another when a ‘shift’ of the reference point occurs. By way of illustration, consider the following examples:

E.g. (a) My train leaves at six p.m. (Simple Present, Indicative)

(b) We are getting married in spring. (Present Continuous, Indicative)

(c) When I see the kids, I’ll send them home. (Simple Present and

Simple Future, respectively, Indicative)

(d) Didn’t I tell you I’d be visiting my relatives (the) next week?

(Future-in-the-Past, Indicative)

(e) Phone me after you have left the office. (Imperative and Present

Perfect, Indicative, respectively)

These examples illustrate the concept of ‘deictic shift’[22], a label given to all the time references occurring in a deictic time sphere other than their original time specification, i.e. they refer to future events, rather than to present ones, although a present tense is used, except for the main clause in example (c), where Simple Future functions as the time anchor for the subordinate. These and others will be dealt with below.

III.4 Alternative Devices for Expressing Futurity

As English has a keener grasp of the concept of time, encoding it not just through the tense inflections that verbs bear, but also through a wide range of time adverbs and adverbial phrases,[23] understandably, there are many difficulties when dealing with English, as a Romanian user of it. What is even more important, is that this formal variety depends either on the content of the utterance (in pragmatic terms, speech acts, like promises, threats, warnings etc.) or on the necessity of accuracy in rendering duration, anteriority, nearness, certainty, projection, etc. Furthermore, there is a general view that time and tense do not represent a one-to-one relationship. Consider the table below that groups all the alternative expressions with a future meaning:

|

Present time sphere |

Past time sphere |

|

•Present Simple (scheduled activities) e.g. The train leaves at 4 p.m. |

•Past Simple (reported scheduled activities) e.g. They said the train left at 4 p.m. |

|

•Present Continuous (personal arrangement) e.g. We’re meeting at 6. |

•Past Continuous (reported personal arrangement, plan) e.g. They said they were meeting at 6. |

|

•Be going to (intention, imminent event) e.g. I’m going to visit him. I think I’m going to faint |

•Be going to (reported intention, imminent event) e.g. She said she was going to visit him. e.g. He realised he was going to faint. |

|

•Be about to (immediate future activity) e.g. Stop fidgeting! The concert is about to start! |

•Be about to (immediate future activity-reported speech) e.g. She asked him to settle down as the concert was about to start! |

|

•Be to (inevitable, predetermined event) e.g. They are to arrive at noon. |

•Be to (inevitable, predetermined event- reported speech) e.g. He explained that they were to arrive at noon. |

|

•Be bound to, be sure to, be due to e.g. The plane is bound to land around 4 p.m. |

•Be bound, be sure to, be due to (reported speech) e.g. Mum told us that the plane was bound to land around 4 a.m. |

|

•Present Perfect (in time clauses, conditional sentences) e.g. I’ll be back after you have finished the work. e.g. If you have finished eating you will be excused. |

•Past Perfect (reported in time clauses, conditional sentences) e.g. He said he would be back after I had finished the work. e.g. Mum said that if I had finished I’d be excused. |

III.5 Overall description of the future forms, in point of meanings and uses

We cannot refer to future events as facts, the same way we refer to past and present, since future events are not open to observation or memory. We can predict with more or less confidence what will happen, we can plan for events to take place, express our intentions and promises with regard to future events. As mentioned many times above, these are modalised, rather than factual statements. This brings forth the matter of future forms belonging to the Indicative mood or not, since this mood is inscribed in the category of realis, a status which has reality in any of its time reference which opposes to the conceptual irrealis content of these forms.[25] This, the morphological and the lexical features shall/will, should/would have, reinforce the viewpoint that English has but two tenses: present and past.

In what follows, I shall adopt another way of organising all grammatical devices that can be employed to refer to the future, so that the process of teaching and learning will be directed towards communicative competence rather than grammar rules description.

i) ‘Safe’ Predictions:

E.g. (1) John will be nineteen tomorrow.

(2) You’ll find petrol more expensive in Romania.

(3) Tomorrow morning I will wake up in this first-class hotel suite.

(4) Tell him Prof. Cressage is involved – he will know Prof.

Cressage.

These are predictions that do not involve the speaker’s volition, and include cyclical events and general truths. Will + infinitive is used, shall by some speakers for ‘I’ and ‘we’[27]. In Romanian they can be translated by Prezent, Viitor Popular and Viitor Propriu-zis, Indicativ:

E.g. (1) John va implini/implineste nouasprezece ani maine.

(2) O sa gasesti/Vei gasi petrolul mai scump in Romania.

(3) Maine dimineata ma voi trezi/trezesc in hotelul acesta de prima

clasa.

(4) Spune-i ca ste implicat profesorul Cressage – va sti cine este

profesorul Cressage.

Will/shall + progressive aspect combine the meaning of futurity with that focusing on the internal process, in this way avoiding the implication of promise associated with will when the subject is ‘I’ or ‘we’. Compare:

E.g. I will (I’ll) speak to him about your project next Friday.

We shall (we’ll) be assessing your project shortly.

[Ii voi vorbi despre proiectul tau vinerea viitoare.]

[Va vom evalua proiectul in cel mai scurt timp.]

This linguistic device is traditionally acknowledge as Future Continuous, but for the coherence and cohesion of the present paper it will be included in a separated category:

ii) Future On-going Events:

This category comprises activities in progress over a period of time in the future:

E.g. (1) With my new job, I will be travelling back and forth across the

country.

(2) Alan will be studying until 5:00 tonight, and then he has to meet

his professor

(3) No doubt at this time tomorrow Nick will be arguing with his

girlfriend.

(4) The headline writers will be wondering endlessly about Mrs

Thacher’s choice of an election date

In sentence (1), the action is recurrent over a period of time in the future; hence the use of the progressive form of will-future is required. In example (2), the activity is in progress up to a point in the future and in the third and fourth examples the activities are on-going at some point in the future.

In Romanian, these utterances appear either in Viitor Propriu-zis or Viitor Popular, Indicativ:

E.g. (1) In noua mea slujba voi calatori/o sa calatoresc de la un capat al

tarii in altul.

(2) Alan va invata/o sa invete pana deseara la 5, apoi trebuie sa-si

intalneasca profesorul.

(3) Fara indoiala, maine pe vremea asta Nick va avea/o sa aiba o

discutie cu prietena sa.

(4) Editorialistii se vor intreba la nesfarsit /o sa se tot intrebe care

este data pe care d-na Thacher a ales-o pentru alegeri

iii) Programmed/scheduled events:

Future events seen as certain because they are unalterable (1) or scheduled (2), (3) and (4) can be expressed by the Present Tense + time adjunct, by will or by the lexical auxiliaries be due to + infinitive and be to (simple forms only). According to L. G. Alexander, the will-form is used particularly in formal written language[28]:

E.g. (1) The sun sets at 20.25 hours tomorrow.

(2) Next year’s conference will be held in New York.

He is due to start university in two months’ time.

He is to marry the future heiress of the throne.

The Romanian counterparts are either Viitor Propriu-zis/Popular, or Present, Indicativ in all cases:

E.g. (1) Soarele apune/va apune la orele 20.25 maine.

(2) Conferinta de anul viitor se va tine/o sa se tina/se tine la New

York.

(3) [El] Va incepe/O sa inceapa/Incepe facultatea peste doua luni.

(4) Se va casatori/ O sa se casatoreasca/Se casatoreste cu mosteni-

toarea tronului.

This use of Simple Present can occur in narrative sequence, or in a context where the future reference is assumed. Such an example is given by Leech[29]:

E.g. Right! We meet at Victoria at nine o’clock, catch the first train to

Dover, have lunch at the Castle Restaurant, then walk to Deal.

The statement suggests an irrevocable decision about the course of the events, due to the Simple Present, as if the enacting in advance of the events takes place. In Romanian such structures are rendered by Prezent or Viitor, Indicativ, since the Romanian tenses do not encode such meanings, rather they are signalled through lexical specifications:

E.g. Bine! Ne intalnim/Ne vom intalni la gara Victoria la ora noua, ne

urcam/vom urca in primul tren catre Dover, luam/vom lua pranzul

la Restaurantul Castel, apoi mergem/vom merge in orasul Deal.

iv) Intentions:

Such situations can be expressed by the semi-auxiliary be + going to + infinitive (1), be + about to (when intent is the purpose of the communication) and the Present Continuous (2).

E.g. (1) I am going to try to get a loan.

(2) I’m about to go home.

We’re thinking of selling our old car.

The ‘going to’ construction is a special case of 1) grammaticalisation and 2) semantic change from an allative (“a type of inflection which expresses the meaning of motion ‘to’ or ‘towards’ a place) meaning to a more abstract and hence more grammaticalised future meaning. Heine et al., 1991, page 70 gives account of this process of grammaticalisation which is a metaphoric extension from what they call ‘a more concrete source domain’ (example 1) to ‘a more abstract target domain’ (example 4):

E.g. (1) Liliy is going to town.

(2) George: Are you going to the library?

Lily: No, I’m going to eat.

(3) George is going to do his very best to make Lily happy.

(4) It is going to rain.

The first example has the allative (spatial) meaning, while the fourth expresses a purely future meaning, between them the two utterances being intermediate – (2) reflects an intention meaning and (3) intention plus a secondary sense, prediction.

Even though this kind of grammatical-semantic shift can offer a hint about the time content of ‘going to’ constructions, there still exist contexts in which the grammaticalisation of this expression does not apply entirely or clearly and which may raise difficulties in rendering English texts into Romanian or the other way round. Consider these examples:

E.g. (5) George is going to buy some champagne.

(6) I am going to study in the library.

On this matter, I am going to favour Vyvyan Evans and Melanie Green’s view,[30] according to which the plausible meaning here is intention (future time reference) rather than spatial motion, as ‘the conceptualiser mentally scans the agents’ motion through TIME rather than SPACE, and this scanning becomes salient in the conceptualiser’s construal because the motion along this path is not objectively salient (there is no physical motion).’ Again, the accuracy of decoding such utterances is given by the extended context, or is subject of pragmatic inference.

In Romanian, the whole situation lies between present and future time reference, the ambiguity rising only starting from the third example on. The disambiguation is ensured by the context, as well.

E.g. (1) Lily se duce in oras.

(2) George: Te duci la biblioteca?

Lily: Nu, ma duc sa mananc.

(3) George are de gand/intentioneaza/are sa faca tot ce-i sta in

puteri ca sa o faca fericita pe Lily.

(4) Va ploua/O sa ploua.

(5) George intentioneaza/se duce sa cumpere sampanie.

(6) Intentionez/O sa studiez/Ma duc sa studiez in biblioteca.

There is still a type of syntactic synonymy between the ‘going to’-future and the will-future, when ‘the intention is neither clearly premeditated nor clearly unpremeditated’[32]:

E.g. (1) I will/am going to climb that mountain one day.

(2) I won’t/am not going to tell you my age.

The same linguists draw a parallel between the two structures highlighting the contexts which are compatible with one of them or the other, but not with both:

the be going to form always implies a premeditated intention plus a sense of previous arrangement, while will + infinitive implies intention alone. This is shown by the following examples:

E.g. (3) I have bought some bricks and I’m going to build a garage.

(4) There is somebody at the hall door. I’ll go and open it

(5) What are you doing with that spade? I am going to plant

some apple trees.

Will + infinitive in the affirmative is used almost entirely for the first person. Second and third person intentions are therefore normally expressed by be going to, as well as in the first person:

E.g. (6) He is going to resign.

(7) Are you going to leave without paying?

In the negative, won’t can be used for all persons:

E.g. (8) He isn’t going to resign.

Or

(9) He won’t resign.

As stated above, be going to implies immediacy, while will + infinitive can refer either to the immediate or to the more remote future:

E.g. (10) Some workers arrived today with a roller. I think they are going

to repair our road.

(11) This is a terrible heavy box. ~ I’ll help you carry it.

The examples built with the will-future cannot be rephrased using the going to structure, since in the first case, the evidence of premeditation is clear, whereas in the second, there is a sense of spontaneity in showing the intention.

Romanian has a few periphrastic structures that can render both English forms, such as: ’a intentiona sa’, a avea de gand sa’, along with Viitor Propriu-zis, or Viitor Popular, Indicativ.

E.g. (1) Intr-o buna zi voi escalada/am de gand sa escaladez muntele

acela.

(2) Nu iti voi spune/N-am de gand sa iti spun varsta mea.

(3) Am cumparat niste caramizi si intentionez sa-mi construiesc un

garaj.

(4) Este cineva la usa din hol.~

Ma duc/voi duce sa deschid.

(5) Ce faci cu sapa aceea?~

Intentionez/Am de gand sa plantez niste meri.

(6) Intentionaza/Are de gand sa demisioneze.

(7) Ai de gand/Intentionezi sa pleci fara sa platesti?

(8) N-are de gand/Nu intentioneaza sa demisioneze.

(9) Nu va demisiona.

(10) Azi au sosit niste muncitori cu un rulou. Cred ca o sa repare/

au de gand sa repare drumul.

(11) E ingrozitor de grea cutia asta.~

Te voi ajuta/Te ajut eu s-o cari.

Some communicative situations require the conveyance of an event posterior to a past moment, named by some linguists ‘prospective past’, this providing a past form constraint to the ‘going to’ form:

E.g. (12) He was going to send the invitations but the guest list was no-

where to be found.

(13) I was going to ask for my money back, but I was advised not to.

(14) Lucy was going to travel round the world when she left school.

(12) Avea de gand/Intentiona/Avea sa trimita invitatiile, dar lista de

invitati era de negasit.

(13) Eu intentionam sa-mi cer/Aveam de gand sa-mi cer banii

inapoi, dar am fost sfatuit sa n-o fac.

(14) Lucy intentiona/avea de gand sa calatoresca in jurul lumii cand

termina scoala.

The Romanian counterparts are built with Imperfect, Indicativ, which bears an aspectual sense – progressive – existent in English too. (As argument for this, see Infra: page 36)

v) Imminent/forthcoming/impending events:

When nearness is needed to be expressed, English usually uses periphrastic structures, be + going to, be + about to + infinitive, be on the point of/be on the verge of + -ing form. When the will-form is used for such purposes, an adverb or adjective (imminent, immediate, immediately, shortly, etc.) has to be present to add the idea of imminence to the futurity reference. Furthermore, in most of the cases, the imminence of the happening is externally or internally signalled:

E.g. (1) It looks as if it’s going to rain.

(2) This company is about to branch/on the verge of branching out.

(3) A decision from the judges is imminent. We will return to the

law court as soon as we have any further news.

The first example displays two meanings, the nearness of a process and the prediction based on present evidence. The other two examples express only the immediacy of the events.

As for Romanian, these can be rendered in various ways, either by periphrastic constructions or by various forms of future (Viitor Propriu-zis, Viitor Popular):

E.g. (1) Arata de parca ar sta sa ploua./Se pare ca va ploua.

(2) Compania aceasta este pe cale/pe punctul de a se extinde.

(3) Decizia judecatorilor este iminenta. Ne vom intoarce/O sa ne in-

toarcem la tribunal de indata ce avem/vom avea vesti.

vi) Arrangements/Plans made beforehand:

First, in most of the cases, English uses Present Progressive to express a definite arrangement in the near future:

E.g. (1) I’m taking an exam in October.

(2) Bob and Ann are meeting tonight.

(3) I’m staying home tonight.

(4) What are you doing next Saturday?

(5) I’m seeing him tomorrow.

This type of future cannot be used with those categories of verbs that do not accept the progressive aspect: verbs of perception, those denoting mental activities, feelings, etc.

Second, the going to – form can also convey this meaning, though there is ambiguity in an utterance like this, since the borderline between intention and plan/arrangement is difficult to draw, both senses implying premeditation. Take these examples for comparison:

E.g. (6) He is going to visit his old friends this weekend.

(7) Our new piano is going to be delivered tomorrow.

The first example can be read either ‘he has the intention of’ or ‘he has planned this’, and the second ‘according to a previous plan’ or ‘there is the intention of’

To be to + infinitive is another way of conveying a plan, though this is specific to newspapers mostly or in formal arrangements:

E.g. (8) She is to be married next month.

(9) The expedition is to start in a week’s time.

When referring to planned events, particularly in connection with travel, Future Continuous can be used:

E.g. (10) We’ll be spending the winter in Australia. (= we are spending)

(11) Professor Craig will be giving a lecture on Etruscan pottery

tomorrow evening. (= is giving)

Romanian has no structural constraints in rendering such meanings, that is, a certain form – whether it is Prezent or Viitor, Indicativ – does not necessarily convey a certain meaning; rather, various forms can be employed in serving the same semantic needs. Compare:

E.g. (1) In octombrie sustin /voi sustine un examen.

(2) Bob si Ann se intalnesc/vor intalni deseara.

(3) Deseara stau/voi sta acasa.

(4) Ce o sa faci/vei face anul viitor in septembrie?

(5) Ma intalnesc/voi intalni cu el maine.

(6) Isi va vizita/Intentionaza/Are de gand sa isi viziteze vechii

prieteni la sfarsitul acesta de saptamana.

(7) Pianul ne va fi/o sa ne fie livrat maine.

(8) Se casatoreste/va casatori luna viitoare.

(9) Expeditia va incepe/urmeaza sa inceapa intr-o saptamana.

(10) Ne vom petrece/O sa ne petrecem iarna in Australia.

(11) Profesorul Craig va sustine/o sa sustina o conferinta pe tema

olaritului etrusc maine seara.

As easily seen in the examples above, English verbal forms not only anchors the action/state on a certain point on the time axis, but this temporal function co-occur with others, in these cases – the idea of plan/arrangement. Conversely, Romanian does not appeal to verbal forms only, when having to associate a supplementary meaning, because the Romanian tenses are not endowed with such functions. It is the context that associates functions/meanings with temporal references.

vii) Predictions:

Simple Future can be employed to make predictions about future, irrespective of the presence of the explicit performatives - verbs that label the speech act (‘think’, ‘assume’, ‘believe’, etc) - or implicit performatives, in which case the speaker consciously makes use of pragmatic inference, so that they can choose the appropriate grammatical structure to render the intended meaning:

E.g. (1) As she grows up, she’ll see that her dislike of Gavin is irrational

even if she can’t admit it.

(2) The procedure is very simple and will be familiar by now.

(4) I think she’ll answer ‘yes’ to every question you ask her.

(5) I shall regret this for the rest of my life!

(6) As we shall discover, the concept of child abuse is an extremely

elusive one and means different things to different people.

(7) My father will probably be in hospital for at least two weeks.

The use of shall for the prediction meaning (examples 5, 6, 7) is rarely used outside the English of Southern England. The canonical use, compulsion, is mainly con-fined to legal and administrative language.

A lot more difficult is with the Romanian language, since there are no grammatical constraints upon what structure to use when rendering this meaning, hence the confusion about which form to use to translate/render such texts into English, since predictions can be rendered by Prezent, Viitor Propriu-zis, Viitor Popular, Indicativ, but without naming what Romanian ‘does with words’. Compare:

E.g. (1) Cand va creste/o sa creasca, va vedea/o sa vada ca toata antipatia

sa pentru Gavin este irationala, chiar daca nu poate s-o recu-

noasca.

(2) Procedura este foarte simpla si, probabil, este/va fi fost clara pana

acum.

(3) Sezonul turistic se (va) deschide pana maine.

(4) Cred ca va raspunde/o sa raspunda ‘da’ la orice intrebare a ta.

(5) Voi regreta/O/Am sa regret asta tot restul vietii mele.

(6) Asa cum vom descoperi/o sa descoperim, conceptul de molestare

a copilului este unul extreme de ambiguu si inseamna multe lu-

cruri, pentru multi oameni.

As this paper is intended for upper-intermediate & advanced students, the description of the five categories of speech acts produced by Searle[33] can be introduced, which would solve the discrepancies between the two languages in point of communicative functions and the grammatical constraints they impose, when it comes to promises, threats, requests, commands, claims, et..

E.g. Mi se pare ca se inchide/va inchide/o sa se inchida si aceasta fabrica

in scurt timp.

Romanian can employ either Prezent or any type of Viitor Propriu-zis, Indicativ, while in English only the will-form or, if present evidence is assumed to exist for such a prediction, ‘going to’-form can be used:

E.g. It seems to me/I believe that this factory will be/is going to be closed

down soon.

Predictions based on present evidence are, therefore, conveyed by the ‘going to’- form:

E.g. (1) It’s going to rain. Look at those heavy clouds.

(2) Help! I’m going o fall!

The years of teaching experience tell me that if students are exposed to the speech act theory, adapted to their learning stage and age, they will handle futurity more easily, which is the objective of any teaching endeavour.

viii) Future anterior events:

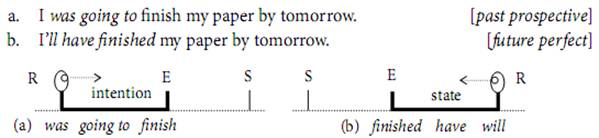

The relation between time and tense has great consequences in the attempts of systematizing grammar; what is more, the interaction between the past and future times gives rise to complex notions to this relation. We may look to a posterior situation from a past reference point (see examples (3), (4) and (5) in iv) and, conversely, from a future reference point to an anterior event. The latter temporal perspective is rendered by future perfect. Günter Radden and René Dirven represent such situations graphically, naming the former past prospective and the latter in the traditional way, future perfect:[34]

Figure The representation of the future actions/states sequencing

They claim that the two situations ‘display near-perfect mirror images’, each involving separate segments of time: speech time (S), reference time (R) and event time (E) and in each (R) being placed further away from (S) than (E). The conceptual difference between the known reality of the past and the projected reality of the future entails different notions of time, an idea sustained by many linguistic studies, especially in cognitive grammar or cognitive linguistics.[35]

By way of further illustration, consider the following examples:

E.g. (1) By the time he is twenty-one, he’ll have become the deputy

manager of the hotel.

(2) The concert will have started before you arrive.

(3) Readers may prefer to wait for the paperback to appear,

by which time most mistakes will have been ironed out.

(4) Chances are you will have stirred things up enough to bring a

question to the surface.

The Romanian language renders these structures rather oddly, for people with an accurate time axis in mind. Not only does it lack the idea of sequence of tenses, which is crucial in English in contexts like the above ones, (in all examples, the present form of the verb in the subordinate clause is required by its temporal nature, while in the main clause the future perfect is used), but it also uses Viitorul Propriu-zis, Indicativ (the Formal Future, Indicative) in both sentences, leaving the connectors to signal the temporal relation between the events. In the last example, however, Romanian uses either the Perfect Infinitive or the Perfect Conjunctive/Subjunctive where English has Future Perfect:

E.g. (1) Pana cand va implini 21 de ani, va deveni managerul adjunct al

hotelului.

(2) Concertul va incepe pana vei sosi tu.

(3) Cititorii ar putea sa astepte sa apara volumul, timp in care cele

mai multe greseli vor fi disparut/disparea.

(4) Exista sansa de a fi pregatit/sa fi pregatit terenul pentru a aduce

in discutie o problema.

As with any English verbal form, future perfect has simple aspect, which designates the repetition of an event in the future before a time limit, and a progressive variant which emphasises duration of the event up to that limit of time and the incompletion of the sequence:

E.g. (1) We’ll have lived here for ten years by next July.

(2) We’ll have been living here for ten years by next July.

Romanian signals duration through lexical units, as the verb has no such category, that is why, both English sentences are translated in only one variant, by means of Present Indicative:

E.g. Se vor implini zece ani in iulie de cand locuim aici.

Or

In iulie sunt zece ani de cand locuim aici.

ix) Past prospective:

When the expected event is oriented from a past reference point, it is expressed by the past corresponding forms of the above phrases. This type of futurity is called Past Prospective[36]:

(2) The most celebrated suburban development involved

Such instances refer to ‘some time in the past [primary time reference] when a future event [become, know, prove – which have secondary future reference] was anticipated, which is to say that the event time for becoming, knowing, proving is out of sequence and is, moreover, future relative to the past narrative time. Such sentences, then, refer to a past situation in the future relative to that primary past: actions or intentions in that past are leading to that future.’ (Noonan, op. cit. page 120)

The same phenomenon can occur with ‘will’-future, would being used as the past form:

E.g. (4) Little did Harriet know that in ten years Waldo would be the

richest man in Frostbite Falls.

Romanian possesses only one structure that can be thought of as the equivalent for English: (a) the Imperfect form of the auxiliary a avea and the Present Conjunctive/Subjunctive of the notional verb. Apart from this, Romanian can also employ (b) Viitor, Indicativ to render such a meaning, lacking the sequence of tense constraints.

E.g. (1.a) Nu este ceea ce credea ca avea sa devina.

Vs.

(1.b) Nu este ceea ce credea ca va deveni/o sa devina.

(2.a) Cea mai cunoscuta dezvoltare suburbana a inlcus ceea ce avea

sa se fie cunoscut dupa 1915 ca ‘Metroland’

Vs.

(2.b) Cea mai cunoscuta dezvoltare suburbana a inclus ceea ce va fi

cunoscut dupa 1915 drept ‘Metroland’

(3.a) Redescoperirea vietii urbane avea sa se dovedeasca un proces

lent

Vs.

(3.b) Redescoperirea vietii urbane se va dovedi un process lent.

(4.a) Nu prea stia Harriet ca in zece ani Waldo avea sa fie cel mai

bogat om din Frostbite Falls.

Vs.

(4.b) Nu stia Harriet ca Waldo va fi cel mai bogat om din Frostbite

Falls.

In such cases, the Romanian learners need to be introduced/to reinforce the concepts of time reference, point of reference, posteriority, simultaneity and anteriority so that they can understand that there is little, if any, resemblance between the English and Romanian syntax. Almost invariably the Romanian learners tend to translate the Romanian (b) contexts by will-future, which is felt to be the English equivalent for Viitor, Indicativ.

x) Requests, offers and promises

Both label two kinds of speech acts, coded by the will-future. Consider the following examples:

E.g. (1) Will you pass me the salt?

(2) Will you lend me your dictionary?

(3) Shall I give you a hand in tomorrow’s contest?

(4) Shall we bring you anything from the journey?

The four utterances are questions in form, but their content points to something else; we have to do with a request/demand (requesting means getting the addressee to commit to making the proposition true, not waiting for information – these speech acts are called directives[37]), in (1) and (2), in that they expect a non-linguistic answer, but an act – the addressee is expected to pass the salt or lend the dictionary, rather than answering ‘Yes, I will’ and performing nothing else. In this case, the cooperative principle would be left aside, the communicative act being null.

In examples (3) and (4) we have to do with a different kind of speech act. Though the answers to these can be linguistic, at a more subtle level, they convey a kind of commitment between the two interlocutors. In this case, they lie among those speech acts labelled as ‘commissives’, together with promises. The difficulty in dealing with these linguistically is that they are indirect speech acts, the accuracy in decoding their meanings depending on the extended context which may overtly point to such meanings and/or on inference, based on cultural convention.

Most traditional grammars describe these types of utterances as containing a modal verb, rather than conveying futurity. Speech act theory rules away the shortcoming resulting from the traditional assumptions and my stating that these speech acts point to an after-the-moment-of-speaking realisation of the content. I will take as arguments the description of these constructions made by Francisco Jose Ruiz de Mendoza and Annalisa Baicchi in Illocutionary constructions: Cognitive motivation and linguistic realization, published in the linguistic series Explorations in Pragmatics, Mouton de Gruyter, 2007. Thus, an utterance like: Will you buy the tickets (tomorrow)? may be read as a question about the future, in the same way as examples (1) and (2) I gave above, with or without an adverbial of time being present. This is because about (1) and (2) we can infer that the request they contain may be fulfilled after the hearer has finished using the salt or the dictionary, respectively, which anchors both situations on the time axis ahead of the moment of speaking.

Things are different with the Romanian language. The most frequent structure used for such purposes contains a modal verb – a vrea:

E.g. (1) N-ai vrea/Vrei sa imi dai sarea?

(2) N-ai vrea/Vrei sa imi imprumuti dictionarul tau?

(3) N-ai vrea/Vrei/Sa-ti dau o mana de ajutor la concursul

de maine?

(4) Vreti/Sa va aducem ceva din calatorie?

These are some more cases which, introduced to the students under the ‘label’ cited in the subheading, reinforce the effectiveness of the functional grammar approach that this paper has attempted to prove so far. This also counts for the organisation of the linguistic material as formal/informal/colloquial, since there are various degrees of politeness when conveying directives, from plain imperatives to formulas including modal-auxiliary verbs, which make the utterance politer through their quality of ‘mitigating devices’ (Mendoza & Baicchi, op. cit. page 107).

A different type of speech acts are promises, described in the linguistic treatises as illocutionary acts that are internal to the locutionary act, in the sense that, if the contextual conditions are appropriate (commitment to carry out what is promised), by simply saying the words, someone performs the act of promising, as well:

E.g. (1) I promise I’ll be there to support you.

(2) I’ll post the letter for you.

The first is a direct speech act – it contains a performative verb, promise, the second is an indirect speech act, as its type is inferred, rather than labelled.[38] With communicative situations as in the second example (indirect speech acts), the translation into Romanian is uncomplicated, but when English is the target language for such speech acts, things become a little more difficult, because the confusion between intention and promise is common in Romanian. Compare:

E.g. Iti voi scrie/O sa iti scriu in fiecare zi.

This sentence can be decoded as intention or promise, by way of inference, depending to a great extent on the extended context. The consequence is the differentiated grammatical treatment of the utterance in English: the former ‘reading’ requires going to-future, the latter – the will-future:

E.g. I’m going to write to you every day. (intention)

I shall/will write to you every day. (promise)

xi) Hopes, decisions:

This category does not display difficulties for the Romanian students of any level, since it carries no ambiguities. In most cases, the verb hope is the explicit signal of the content of the utterance, whereas the meaning ‘decision’ is generated by a rather unequivocal context.

E.g. (1) Sper ca ii va placea/o sa ii placa Londra.

(2) Spera ca se va obisnui/o sa se obisnuiasca/are sa se obisnuiasca

repede cu trezitul devreme.

(3) Nu imi place culoarea. Nu cumpar/voi cumpara/o sa cumpar

tapetul acesta.

(4) Traducerea aceasta este foarte buna. O sa cumpar/Voi cumpara

volumul acesta de versuri.

The functional approach of the matter I am proposing will simplify the transfer from Romanian into English, particularly due to the wide range of grammatical devices which can convey not only these meanings these (Viitor Literar, Viitor Popular, Prezent-Indicativ) and to the lack of structural overlapping between the two languages that I am bringing face to face in this paper; conversely, the formalist approach, which takes into account the grammatical structure, would make things more difficult for the same reasons I stated above, plus the use of only one tense form in English for such meanings, namely the will/shall-future:

E.g. (1) I hope he’ll like London.

(2) He hopes he’ll get used to waking up early.

(3) I don’t like the colour. I won’t/shan’t buy this wallpaper.

(4) This translation is great. I’ll buy this poetry volume.

III.6 Futurity in complex sentences:

i) Clauses of time:

The Romanian students learn English verb tenses one by one, so when they learn how to use adverbial clauses of time in the future, they are puzzled. Things are different in complex sentences in comparison with the independent ones, syntactically speaking, though from the semantic point of view there are no major variations. The explanation of this state of affairs was given by many linguists, among whom I mention Tregidgo, P. S.[39], Marianne Celce-Murcia and Diane Larsen-Freeman , and to whose view I subscribe.

Thus, in The Grammar Book, Celce-Murcia and Larsen-Freemen take a historical approach of this linguistic issue. They begin the discussion with an example which I am going to cite here, as an appropriate starting point:

‘John will travel to Europe this summer. After he returns to the States, he will begin graduate work in Management.’

They explain the reason why the present tense is used on the future time axis as follows: first, Old English had two tenses, present and past, and present tense was used in order to express future time. Second, older forms and orders are retained longer in subordinate clauses than in independent clauses (ibid.). If the present tense was used in order to express future time, it is possible that it can be used in adverbial clauses of future time.

In the same way, Tregidgo (1974: 192) corroborates this point by using ‘the notion of tense-subordination,’ explaining that ‘it means that the view point of the tense-form (the subordinate tense) is based on the viewpoint of another (governing tense)’. In other words, the main clause tense affects the subordinate one. For example, ‘When you put your coat on, you will feel warmer.’ He rewrites this complex sentence into compound sentences, such as ‘You will put your coat on and you will feel warmer.’ The first sentence ‘you will put your coat on’ is closely related to the second one ‘you will feel warmer.’ He concludes, ‘If we subordinate the first clause to the second, we also subordinate the first tense to second.’ (Tregidgo, 1974: 195) His explanation is clear and this is how this structure works in some sentences from newspapers and movies. In the Daily Local News, on June 9, 2002, there is an article that reads:

E.g. When the school bell rings for afternoon dismissal today at Bishop

Shanahan High School, students will exit the historic Catholic high

school for the final time.

Beginning this fall, an estimated 950 Shanahan students will attend

a newly constructed 1,200 student capacity high school in Downing-

town.

The present tense of rings here does not indicate present time, but the same time, or very close to the time of students’ leaving the high school. The use of will ring is not possible here, because the clause describing the action of the bells has been subordinated to the clause describing the action of the students by the use of the word when.

When bringing Romanian and English face to face, things get complicated because the two languages encode such examples differently. Compare:

E.g. (1) He’ll phone his friends as soon as he arrives at destination.

(2) When we meet, I’ll explain everything.

(Will-future, in the main/matrix clause and Present Simple, in the

subordinate clause)

Vs.

Isi va suna/O sa isi sune prietenii de indata ce va ajunge/o sa ajunga la destinatie

Cand ne vom intalni/o sa ne intalnim, iti voi explica/o sa-ti explic totul. (Viitor, Indicative in both sentences)

This ‘rule’ applies in each case of time clauses, when the event time of both matrix/main and secondary clause are concomitant, irrespective of the conjunction (when, before, whenever, as soon as, the moment, until, the day) that connects the two clauses. By way of illustration, consider these examples:

E.g. (1) He’ll finish his project before the manager asks for it.

(2) The moment we get there, we’ll check in.